Papers

Reports and analyses from around the world are presented at MW2005.

| Workshops |

| Sessions |

| Speakers |

| Interactions |

| Demonstrations |

| Exhibits |

| Best of the Web |

| produced by

|

| Search A&MI

|

| Join our Mailing List Privacy Policy |

Recontextualizing the Collection: Virtual Reconstruction, Replacement, and Repatriation

John Tolva, IBM, USA

Abstract

This paper addresses the evolution of the technologies of virtual representation in the cultural milieu. Using IBM project case studies from a decade of experience in this field, the paper brings to the fore the ways in which these technologies both reify and challenge traditional ideas of what a museum is or should be. The paper examines the evolution of simple virtual representation (exemplified by the Hermitage Museum project) to modeled reconstruction and deconstruction (exemplified by the Digital Pietą project) and thence to virtual replacement of artifacts in situ at their point of creation or discovery (exemplified by the Eternal Egypt project). The paper concludes with a look forward to the concept of virtual repatriation between countries and inter-organizational 'sharing' of artifacts between museums.

Keywords: virtual, reconstruction, replacement, repatriation, content management, context

I. The Context of the Museum

Virtual reconstructions of archaeological sites and artifacts have become commonplace in the cultural heritage domain. Repairing damaged works, re-erecting structures, or providing conjectural models of items lost to history – there are many examples of the ways in which virtual archaeology supplements and enhances out understanding of cultural heritage. However, new 3D scanning and modeling technologies, together with distributed content management and enhanced methods for accessing these virtual representations, have important consequences for museums, consequences that force us to confront the nature of a museum as a collection of artifacts separate from the cultural-historical matrix from which they originated.

1. Tools Of Representation

All museums are places of technologically-enhanced representation. At its most fundamental level, a museum is a place for the re-presentation – the presenting again – of something created, used, or identified with someplace else. Many technologies or tools assist in this enterprise. Plate glass, cases, framing, interior architecture, lighting, climate-control, and signage combine to form a sometimes surprisingly high-tech, if mostly transparent, "machine" for the presentation of a cultural artifact, artwork, or other exhibit. Certainly more complex mechanisms exist. Interactive technologies both in physical space and on-line enable museums to act as platforms for the creation of an experience (Hein 2000). In the manner that a theater stage is a kind of machine for the production of an experience or a run-time application is a virtual machine for enabling lines of code to be actualized, the museum today operates as an enabler of visitor experience. For many museums and cultural organizations, this experience is made possible by providing context. But it has not always been this way. As Brad Johnson puts it,

The user experience has crept from one extreme to the other. From the Webmaster's directory structure full of data, to the documentary filmmaker's online QuickTime narrative, the brief history of the Web has offered users the full spectrum of intermediation. (Johnson 2003).

One way of approaching the history of representation in museums is thus to chart the development of the tools used to create context.

Ironically, if extrapolated to extend to its intended target, the trajectory of the intermediation Johnson mentions points to a complete technological disintermediation of the visitor experience: we want context to be created in ways as transparent as plate glass. If a collection is artifact-based, for example, visitors are far more likely to privilege the viewing of these objects over reading or looking at secondary materials, though these materials may be highly valuable. Thus the context-generating tools that work most effectively in this scenario are today largely audio-based, enabling a 'heads-up' experience. As another example, if an exhibit seeks to juxtapose present and past (as many do), often a layering or augmentation of the physical artifact with virtual information can be the most intuitively understandable method for delivering contextual information. A last example – well-articulated in recent years – is the 'technology' of storytelling. In drama, the fourth wall is the tool used to foment suspension of disbelief, the ultimate 'transparent' experience. It is similarly used in museum exhibits to help visitors make personal connections, to target information to specific user groups, to compete with other forms of entertainment, or merely to efface discontinuity between elements in a collection. As such, narrative is arguably the greatest context-making device in use in museums today. The twist is that in the virtualized museum experience, the modes of interaction reach right through the fourth wall to pull the visitors in closer.

2. Virtualized Experiences

The term virtualized experience is here used in the broadest sense. Certainly on-line exhibits are contained in this term. But most experiences inside the physical buildings we call museums have been virtualized to some degree too. That is, even the most traditional museums have been technologically augmented through a virtual representation of subject-matter. Informational signage, detailed close-up images, audio guides, tour guides, even the easels of artists allowed to study and replicate artwork inside the museum – these are all low-tech re-presentations of the core collection. Even so, neither the on-line museum nor its physically-embodied counterpart are completely virtual museums: they retain aspects of one another. But we may usefully call both virtualized entities.

What are the characteristics of a virtualized cultural experience? Though there are plenty of non-computer-based modes of virtualization, I will limit the description here to those that are digital, multimedia, and interactive. Likewise, the virtualization of museum services – on-line ticketing, on-line shops, etc – though vital to the museum as a business, is not primarily concerned with re-presenting the collection or providing context to the subject matter and so will not be discussed here. Looking back on the last fifteen years of cultural computing, we find certain trends emerge. The trends are philosophical as much as technological and, though they are presented here in chronological sequence, they are not linear in their development. There is considerable overlap

The first trend is that of strict representation. It is typified by on-line collections and exhibits, the now-common CD-ROM-based or Web-based supplement to a portion of the main physical collection. The origin of this form of virtualization often can be found in preservation and documentation efforts that preceded the emergence of multimedia end-user technologies of CD-ROM and the Web. Representation in some form – usually the capture of two-dimensional images – is the overriding task; 'bringing the collection to the world' or creating a digital simulacra of the physical collection (though not necessarily the experience of being in the physical space) is the goal. Representation provides context mainly through description or by letting the flexibility of on-line grouping and juxtaposition imply contextual relationships between elements (Freedman 2003).

The second trend is one of reconstruction. For at least the last ten years, virtual archaeology and digital reconstruction of artifacts have been important tools for the management and presentation of cultural heritage. This mode of virtualization has a more complex goal than representation as it seeks to show what no longer exists or what exists in a different state. As a mode it is necessarily context-generating, adding a layer of interpretation and even artistry to the pre-existing represented element. In more advanced types of reconstructive virtualization, often termed augmented reality, the interpretive layer co-exists with the physical element through projection on to the surface of the element or by dynamic overlay in a semi-transparent head-mounted display. Heavily dependent on three-dimensional imaging – either by direct scan or by modeling – the computing requirements for this kind of virtualization are non-trivial and often limit the degree to which it can be presented on the Web.

Presentation and preservation of artifacts in a physical museum setting necessarily removes them from their original setting. It follows that a useful way to provide a superior visitor experience is try to mitigate this decontextualization by re-situating a collection in the milieu of its creation, usage, or discovery. This third trend is defined as a replacement of museum artifacts in situ. It is a component of virtual archaeology, though it differs from a purely archaeological approach in how it capitalizes on the juxtaposition of the current museum setting and information base with the re-placed setting and information base. Being able to cross-reference the two, to choose one's type of mediation, is where the most value in this mode of virtualization is to be found. In addition to replacement, there is also a related mode of re-collection, the bringing back together of elements from previous physical groupings of elements. Examples of this include re-grouping virtually all the items found together in a buried cache or recreating collections virtually according to their presence in the collections of previous owners. Two-dimensional and three-dimensional representation and reconstruction are the building blocks for experiences such as these, but the real enabling technology is a flexible content management system and presentation layer. When cultural elements – people, places, and things – are represented digitally and stored in a systematic, standardized way, the malleability of their presentation increases exponentially. Certainly in situ replacement or re-collection can be achieved without a centralized content management system, but the extensibility of such a virtualized experience is greatly limited without one.

The final mode concerns the creation of meta-museums through inter-organizational sharing of content. It is no great leap technically to move from virtually-reorganized collections to virtualized collections that span multiple institutions. A distributed content management system is a prerequisite for such an experience as it is the fulcrum that enables collaboration among different organizations. The leap required is rather political since the nature of the technology is to foreground the relationships between the cultural elements and not the relationships of the elements to their current physical location and organization. Trickier still is the concept of virtual repatriation, the bringing together of cultural elements in the country of their provenance. The difficulties come not only from the political issues surrounding the 'return' of objects from one country to another, but also from the difficulty of reaching definitive, scholarly consensus on a given object's actual provenance. Yet it is precisely these difficulties that make meta-museums and virtual repatriation such effective experiences. Combining high-fidelity representation, distributed content management and workflow, and digital rights management, partner organizations can created a virtualized experience that generates a whole new level of context for their subject-matter. In many ways this focus away from a collection's physical storage location is a focus on the needs of the end-user. Visitors desire an experience of the subject matter unconcerned with the peculiarities of any one institution's acquisitions history or classification scheme.

II. Evolution and Trends

The IBM Corporation has over a decade of experience working with cultural organizations around the world. As a global technology and services provider with broad resources at its disposal, IBM has brought a great diversity of solutions to bear in the pursuit of virtualized experiences. Looking back on selected projects over the past decade enables a more concrete understanding of the emergence of the trends identified in the previous section. Far from a deterministic survey of the field of cultural heritage informatics, these case studies seek to show the interrelation of the technological and non-technological aspects of the overall museum experience. This section concludes with a look forward in an attempt to divine the next trend from those that precede and will no doubt overlap it.

1. The Hermitage Museum Project

In 1997 the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia, and IBM embarked on a two-year project to develop three end-user applications in support of the museum director's vision of the museum as it entered the 21st Century. The plan called for the development of a Web site (http://www.hermitagemuseum.org) built upon a digital library database, an education and technology center featuring multimedia courseware, and visitor information kiosks placed throughout the museum. A repository of thousands of high resolution digital images from the Hermitage collection formed the hub of the solution as it provided the management system for the main content for each of these applications. To develop the image archive, an image creation studio was outfitted with an IBM Pro/3000 scanner and accompanying processing system for retouching and derivative generation.

Upon launch in 1999, the project received accolades for the quality of its digital imagery and the breadth of its functionality on the Web site. Visitors to the site could (and still can, of course) perform keyword searches, assemble complex searches, search by color and shape, or browse one of the twelve categories of artifact. The taxonomy of the collection was fixed and hierarchical, built for scaffolded knowledge acquisition, not serendipity (see figure 1).

Fig 1: Artwork categories of the Hermitage Museum Digital Collection

The digital images were by far the most important element of the user experience on the Web site. Digitally watermarked images were available in two sizes and via a Java-based zooming applet (see figure 2). Descriptive information could be found further down the page while intra-collection relationships were defined primarily by attribute similarity (same artist, same theme, etc).

Fig. 2: High-resolution 'ZoomView' applet

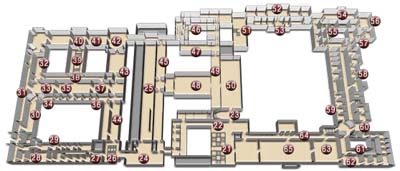

From the beginning the project was representative in nature. That is, re-presenting the Hermitage treasures digitally was the means to the end of opening the museum to a global audience. Indeed, creating a digital proxy for the actual museum – largely inaccessible to much of the West for so long – was an unstated but pervasive goal. An extensive virtual tour from nearly every vantage point was created for the palaces in which the collection is housed (see figure 3).

Fig. 3: Museum virtual tour floorplan showing panorama nodes

Peering through the lens of the years since the project launched, it is apparent how much of the development was suffused with 'archival' nomenclature: we created a Digital Collection using Digital Library software and afterwards published an article called Populating the Hermitage Museum's New Web Site (Mintzer 2001). The design philosophy was very much one of replicating a physical archive or repository. There is no value judgment implied here. Digital archives are fundamental, necessary, and extremely useful. The question is whether the archival nature of the project was just a reflection of the needs of the museum or an outgrowth of a database-centric approach to the project. It is difficult to say unequivocally. One way to approach this question is to consider the possibility that the Hermitage Project is an example of the first step in an evolution of virtualized experiences that parallels changing attitudes towards visitor experience in general in the larger museum community. Just as the notion of what a museum is has evolved over the last two centuries from a wunderkammer-like assemblage of artifacts to its current incarnation as an interactive locus of self-directed or explicit education, the Hermitage Project may represent the beginning of the evolution of the virtualized museum from simple repository to a complex, media-rich, story-based experience (Tolva and Martin 2004).

2. The Digital Pietą Project

The which-came-first question from the Hermitage – did the representational, repository nature of the site grow from the database-centric design or vice versa? – is easy to answer for the Digital Pietą Project (http://www.research.ibm.com/pieta). The art historian Jack Wasserman approached IBM with a well-conceived idea to scan Michelangelo's Florentine Pietą in three dimensions. Wasserman's goal was both to enable a full documentation of the sculpture for posterity and to permit him to test some of his own theories about the statue's creation and re-creation. In short, the goal was to recontextualize the artifact through a virtualized reconstruction. But the story of Michelangelo's sculpture was one of deconstruction and reconstruction well before being virtually reconstructed by IBM and Wasserman. We know that Michelangelo began the Florentine Pietą in the 1550's, purportedly as his own tomb monument. What is not known is why Michelangelo decided to break off parts of the sculpture before abandoning it or why, shortly before dying, he permitted a student to repair and partially finish the statue (Bernardini 2002). By producing a detailed three-dimensional model, Wasserman hoped to validate his theories about these questions (see figure 4).

Fig. 4: Pietą model showing the damaged and repaired segments of the sculpture

The Digital Pietą project exemplifies the trend identified as reconstructive virtualization. The three-dimensional model achieved more than a representation of the stone sculpture (though this accomplishment in itself is highly useful for measurement, analysis, and preservation). Digital representation was merely the step which enabled manipulation of the artifact, permitting Wasserman:

to view the statue in the environment Michelangelo intended, to examine it without the pieces Michelangelo removed, and to analyze the detailed tool marks in the unfinished portion of the work (Bernardini 2002)

As a tool, digital reconstruction permits modes of inquiry that would not be possible without virtualization, but it also represents a layer of interpretation which may seem to be a 'thicker' type of mediation than simple representation.

Fig. 5: Pietą model placed in an elevated niche as it might have looked had it been completed and installed as a tomb monument

The results of the project were published in 2002 with an accompanying CD-ROM permitting readers to manipulate the digital model in a customized viewer application. In addition, a kiosk presenting the IBM work and its part in Wasserman's study has been on display in museums throughout the US and Europe.

3. The Eternal Egypt Project

Though the Digital Pietą Project used a virtualized model to imagine placements and environments that the sculpture might once have been intended for or viewed in (see figure 5), replacement was not the primary goal of the effort. A more comprehensive example of digital replacement of artifacts can be found in the Eternal Egypt Project (http://www.eternalegypt.org), a collaboration of the Egyptian Center for the Documentation of Cultural and Natural Heritage (CultNat), the Supreme Council of Antiquities, and IBM, launched in 2003. Eternal Egypt shared the same nominal goal as the Hermitage project – to bring the cultural treasures to the world, virtually. Yet, from the beginning Eternal Egypt was conceived not as a museum project but as a cultural project for all of the country of Egypt.

Treating the country as a single museum had many consequences. First, the project had to represent the cultural heritage of Egypt across multiple millennia, using several thousand elements (artifacts, people, places) submitted by over a dozen museums and archaeological sites. Naturally a Web site was created to allow easy access to this information. Unlike the Hermitage's use of artwork type categories as the primary means of navigating the repository of information, the modes of exploration on Eternal Egypt reflect the advance of technologies of Web presentation, a more robust architecture of the user experience, and a belief that the relationships between elements can often provide an effective navigation system. The project used storytelling to ensure that the experience of the Web site was not one of thousands of discrete, undifferentiated chunks of data. Narrative arcs linked elements together into compelling threads, providing an organizational undercarriage for the repository of data.

The second consequence of building a project around the idea of a unified cultural heritage was the need to create technologies that would bring the stories and functionality of the Web site into the museums and archaeological sites around Egypt as if they were part of one institution that the visitor was merely strolling through. To this end, a PDA-based Digital Guide was deployed in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo to deliver deep, on-demand context to artifacts in its collection. Information from museums and places outside the Cairo museum was used to explicate the collection contained within the museum walls. The Digital Guide was also deployed for cellphone access so that visitors could use their own devices and move out of one physical environment (the Cairo museum, for instance) to anot her (say, the pyramids) on the same virtual tour.

The most important consequence of the country-as-museum philosophy was the ability to use advanced scanning and presentation technologies to recontextualize artifacts by placing them in their original 'found' state. The fullest example of this in Eternal Egypt is the replacement of the artifacts from the tomb of King Tutankhamun into a three-dimensional model of the now-empty tomb. With the exception of an outer sarcophagus and the mummy of the king himself, all the tomb's artifacts now physically reside in a few dozen rooms in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. When Howard Carter first discovered the tomb in 1922, he assiduously photographed the artifacts in the four small rooms and descending corridor. (Enlarged versions of these stunning photos adorn the galleries that contain the artifacts in the museum, a low-tech virtualization of the space.) These photographs, together with the two- and three-dimensional scans and models of the artifacts, enabled the project team to recreate the tomb as Carter found it. On the Web site one may navigate the tomb virtual environment from one of nine fixed vantage points. Browsing the collection as it was found – and intended to be for all eternity – offers users a glimpse into the functions of many of the artifacts (see figure 6). Statues are seen to be 'guarding' doorways; sarcophagi are nested like matryoshka dolls; there is evidence of an aborted tomb robbery. The replacement affords an entirely new perspective on the artifacts on display in the glass cases of the museum.

Fig. 6: Artifacts from the Tutankhamun collection in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo replaced in a virtual replica of the tomb in the Valley of the Kings

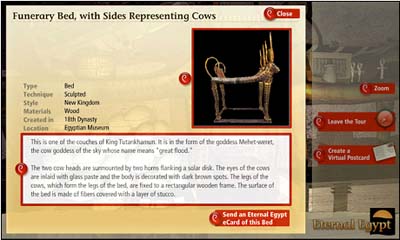

On the Web site, seamless transitioning from one node to another is not possible, given the heavy computing burden of real-time 3D graphics and bandwidth limitations. However, a kiosk version of the re-populated tomb has been developed, and it does employ real-time rendering of the virtual environment. In the kiosk version, users can explore the tomb any way they like, moving in almost any direction. Closer inspection of artifacts is facilitated by a semi-transparent overlay card that displays a subset of the information from the Web site (see figure 7). This overlay functions as a kind of virtualized augmented reality: you move about wherever you like and information is provided to you in a heads-up manner. One can easily envision a system that uses this same content and functionality to repopulate the actual, empty tomb using projection or a head-mounted display.

Fig. 7: Informational overlay from the kiosk version of the Tutankhamun virtual environment

The recreated tomb of Tutankhamun is no more valid an organizational framework than the actual collection in Cairo. There is no single virtualization that offers all the context available. Yet there are certain privileged perspectives. In the museum, the artifacts are arranged mainly to permit the most visitors to experience them. Visitor throughput, issues of collection protection and security, and some thematic groupings offer an organizational framework inside the museum. In a virtualized museum, however, this is but one of many possible frameworks. Technology has progressed to a point where visitors are empowered to select from multiple context-generating frameworks. With such tools at their disposal, visitors can synthesize their own meaning by viewing cultural artifacts from multiple perspectives.

4. Future Directions: The Flexhibit Concept

Advanced content management systems and presentation technologies now enable an almost endless re-collection of artifacts and artwork. When a collection is partially or completely virtualized, it opens up a wide range of possibilities for rethinking the within-the-walls nature of the museum. The Guggenheim.com initiative, Eternal Egypt, and the TryScience project all use digital content from multiple organizations to create a meta-museum. More than portals to constituent organizations' sites, the best of these virtualized museums actively integrate their content to create an experience greater than the sum of its parts.

The Greater Palace Museum Project, a newly-established partnership of IBM and three museums in China and Taiwan, will offer an opportunity to explore the possibilities of a comprehensively re-collected set of artifacts and artwork. Though the project is only in its beginning stages, the concept is simple: to virtually bring together the collection of the former palaces of the Forbidden City in Beijing. Displaced through invasion and conflict, the treasures from the Forbidden City are now contained mainly at the Palace Museum in Beijing, the Nanjing Museum in Nanjing, and the National Palace Museum in Taipei. Geopolitical and institutional realities disallow a physical re-collection of all these artifacts, but scanning and advanced 'in-museum' display technologies point towards the rich context that a merger of physical space and virtualized information will provide. Indeed, other institutions with Qing- and Ming-era artifacts around the world can participate in the virtual re-collection by way of a distributed content management system.

At the heart of a system that can enable such an undertaking is the concept of the flexhibit, a set of integrated tools for enabling truly configurable virtual, real, and hybrid spaces. Because of the continuing evolution of the story of a museum's collection, all of a museum's facilities (from the physical space to the digital channels) must be able to adapt and respond to change. The flexhibit provides a language for creating exhibits that can be experienced across a range of installations. Modular, adaptive, story-based, exploratory, and personalized, the flexhibit is the latest stage in the evolution of the many trends – representation, reconstruction, replacement, and re-collection – that have characterized virtualized museum development over the past decade. Because none of these modes of virtualization provides a definitive perspective on its subject matter, they have supplemented ,rather than supplanted, one another. The goal of projects based on the flexhibit concept is to provide as many contextual frameworks for the user/visitor as possible.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Jack Blanchard for his articulation of the flexhibit concept.

References

Bernardini, F., H. Rushmeier, I. Martin, J. Mittelman, and G. Taubin (2002). Building a Digital Model of Michelangelo's Florentine Pietą. IEEE Computer Graphics and Applications 22(1), 59-67.

Freedman, M. (2003). Think Different: Combining Online Exhibitions And Offline Components To Gain New Understandings Of Museum Permanent Collections. In D. Bearman and J. Trant (eds.). Museums and the Web 2003: Proceedings. Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics, 2003. last updated March 12, 2003, consulted January 21, 2005. http://www.archimuse.com/mw2003/papers/freedman/freedman.html

Hein, H. (2000). The Museum in Transition: A Philosophical Perspective. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Johnson, B. (2003). Disintermediation and the Museum Web Experience: Database or Documentary – Which Way Should We Go?. In D. Bearman and J. Trant (eds.). Museums and the Web 2003: Proceedings. Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics, 2003. last updated March 12, 2003, consulted January 19, 2005. http://www.archimuse.com/mw2003/papers/johnsonbrad/johnsonbrad.html

Mintzer, F., G. Braudaway, F. Giordano, J.Lee, K. Magerlein, S. D'Auria, A. Ribak, G. Shapir, F. Schiattarella, J. Tolva, and A. Zelenkov (2001). Populating the Hermitage Museums New Web Site. Communications of the ACM 44, No. 8, 51-60.

Tolva, J. and J. Martin (2004) Making the Transition from Documentation to Experience: The Eternal Egypt Project. In International Cultural Heritage Informatics Meeting Proceedings. Berlin: Archives and Museum Informatics.

Wasserman, J. (2003). Michelangelo's Florence Pietą. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Cite as:

Tolva, J., Recontextualizing the Collection: Virtual Reconstruction, Replacement, and Repatriation, in J. Trant and D. Bearman (eds.). Museums and the Web 2005: Proceedings, Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics, published March 31, 2005 at http://www.archimuse.com/mw2005/papers/tolva/tolva.html

April 2005

analytic scripts updated:

October 2010

Telephone: +1 416 691 2516 | Fax: +1 416 352 6025 | E-mail: