Fig 1: The (ECHO) Education Through Cultural And Historical Organizations logo

Introduction

It is a truism bordering on the trivial to say that in the 21st century the world is more closely connected than ever. Communication is cheaper and easier than at any time in world history. It does not follow, though, that we understand each other when we communicate. We have the tools; now we have to learn how to use them to promote understanding and fruitful interaction.

Fig 2: ECHO partner locations

ECHO (Education Through Cultural and Historical Organizations), a partnership of six widely dispersed cultural institutions, fosters that learning. Individual missions vary, but the ECHO partners all seek to enhance appreciation of regional heritage; to facilitate dialogue and understanding between people; and to provide life-enhancing educational opportunities in and out of the classroom. Through this dialogue, communities are better able to enter the global marketplace, bridging divides of geography, background, and age, while strengthening local culture.

Fig 3: Native American performer Nakotah LaRance performs traditional hoop dance at the Peabody Essex Museum, 2007

Since its founding in 2001, more than 150 distinct ECHO initiatives have generated over 1,500 exhibitions, events, and public programs – affecting more than four million people. Through those initiatives, ECHO has:

- received 3 million Web visits;

- engaged 580,000 individual program participants;

- catalogued, conserved, and stabilized over 33,000 objects, images, and historical documents for future generations;

- produced 35 documentaries on indigenous and locale-specific culture, art, and history, of which several have been broadcast over public or public access television stations;

- served 244 individual schools (including 100 charter schools), with programs for 100,000 students;

- reached 5,777 life-long learners through non-school educational programs;

- fostered 191 partnerships with sub-recipients of ECHO funding and other community-based organizations;

- given 584 interns of diverse backgrounds practical, on-the-job training in the vibrant and growing museum/cultural communications sector, while providing much-needed diversity to the pool of qualified talent;

- supported 107 Research Fellows pursuing academic research in partner collections;

- hosted 366 teachers at Teacher Institutes, for teachers learning Native and locale-specific ways of life and developing lesson plans and curricula to bring those experiences to their students.

The impact of ECHO is felt most strongly by those on the ground: teachers who teach what they have learned from others; students who develop skills and credentials for the cultural workplace and beyond; people of all ages who, opening themselves to other traditions, discover their own in the process.

The pride of the people was palpable! The dancers in full Native dress, the beating of the drums, the chanting of the singers immediately immersed me in this culture and its people. . . . I will be a better teacher for having had this experience. I know I will be more patient with the E(nglish) L(anguage) L(earner) students and their parents, for I have a different understanding of their experience. ( Nancy D. , New Bedford teacher/participant in Southcentral Alaska Cultural Institute [ANHC])

Ideas I have taken away from this day were: limiting impact; finding balance; the importance of myth, story, and belief; and the elders’ understanding of their world, in the context of the world we all live in today. (Beth B., a Salem, MA middle-school teacher and curriculum specialist, during an ANHC Teacher Institute)

From students:

This internship reconnected me to my roots and ancestors and inspired me to pursue a career as a researcher and historian” (Jessica E., Museum Action Corps intern, PEM).

I learned the difference between an easily broken stick (a weak leader) and a house post (a strong leader). I’m not afraid to speak in front of people. I use all the knowledge from my school, my family, and my ancestors, and try to make them proud of me. I learned all these things from this trip, and I am very grateful. (Destiny M., Hawaiian charter school student participant in Multicultural Youth Leadership Conference, ANHC.)

From other participants:

It’s good to try to ikuk (scrape and tan hides), like my aaka (grandmother) used to do (Anonymous participant in Iñupiaguniqput Sivunmuutilugu (Carrying Our Iñupiaq Ways Forward), a workshop of the Iñupiat History, Language, and Culture Commission, NSB).

ECHO has successfully developed culture- and place-based educational approaches firmly grounded in national and state standards. The educational future of our nation will be written in the language of long distance, public/private, and community-based partnerships, for which ECHO programs are nationally important models. ECHO creates and tests new roles for museums as vital centers for conversations about our culture. By basing its lessons in the communities and cultures from which they spring, employing a mix of traditional and cutting edge practices and technology, and reaching people where they live, ECHO provides education that works.

Current ECHO partners:

- Alaska Native Heritage Center (ANHC), Anchorage, Alaska

- Bishop Museum (BM), Honolulu, Hawai'i

- Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians (MBCI), Philadelphia, Mississippi

- New Bedford ECHO Project (NBEP), New Bedford , Massachusetts

- North Slope Borough (NSB), Barrow, Alaska

- Peabody Essex Museum (PEM), Salem, Massachusetts

Although not explicitly stated in the founding legislation, ECHO is also self-evidently a partnership of Native and non-Native institutions working together to create programming relating to the interaction of Native and non-Native cultures, applicable on a national scale.

Advantages and Challenges

ECHO has certain structural advantages. Our partners are located across the country and through a wide range of racial, ethnic, educational and economic strata. Our institutions’ in-house capacities and resources include legal advisors; researchers in botany, geology, astronomy and arctic and equatorial marine science; educators in both museums and classrooms; cultural expertise in both first nations and Euro-American traditions; Congressional contacts, including ex-staffers, full-time government affairs personnel, and support from our states’ senators and congresspeople; multi-media production capabilities; a publishing house; hunters and fishermen; craftspeople; native speakers of dozens of languages; and graphic and Web design staffs, along with many, many other specialties. By now we have had five years’ experience in working together on projects such as this one. And we have federal funding authorized in law and administered by the Department of Education.

We also have certain built-in challenges. We are geographically dispersed, so face-to-face meetings are expensive and hard to schedule. Our institutions are of different types with different missions. We include in our partnership museums of art, history and science, a Native heritage center, a municipality, and a sovereign nation. In age our institutions range from 200 years to not yet built, and in financial scope from five or six million dollars a year to hundreds of millions. ECHO occupies widely different positions within our parent organizations, from a major pillar of some institutions to a minor supporting element at others. Political and personnel shifts within each parent entity can result in significant, occasionally wholesale, turnover in representatives to group meetings or discussions, and shifts in institutional priorities for the project.

Our greatest advantage, but also the characteristic most difficult to analyze and understand, is our wide range of world views, histories and values. Some of us live every day with the consciousness of hundreds of years of undeniable oppression, injustice, and even genocide; some have fought to retain a staunch independence at extraordinary communal cost of marginalization; some are fully immersed in the dominant Euro-American culture with little institutional mandate to address social wrongs on a national scale. Generating consensus or even mutual comprehension in such a group is not easy, nor always successful. Decisions in our group require consensus, not only because traditional Native decision processes tend to work in that way, but also because strongly divergent impressions of history and reality have to be unwound and understood before we can go forward with confidence: too often we find that a voice not raised at a meeting masks a fundamental variance in perception or intent, or a voice raised too quickly drowned out a viewpoint slower to emerge. And yet, inevitably, issues left unexplored emerge later.

Aims

The present investigation surveys ECHO’s efforts to present material from culturally disparate and geographically dispersed sources representing Native, Euro-American and mixed communities and institutions as authors and participants in creating content. It centers around our effort to re-create our main Web site. The site should do two major things:

- provide content produced by ECHO partners, whether new or archived, reflecting our awareness, history and commitment to cross-cultural understanding and communication

- act as a forum for members of our communities, both virtual and actual, to create and present their own cultural understanding.

Since this is a work still very much in progress, this paper will be an examination of history, principles and approaches based in our collective experience, rather than a final report of results.

History Of ECHO Web Projects

The Web has been central to ECHO’s existence and practice from the start. Our geographic dispersal makes Internet communication a necessity. Our founding legislation requires us to create cultural programming and use “modern technology, including the Internet, to educate students, their parents and teachers” about historic and contemporary links between Native and non-Native peoples. Given that we are federally-funded, we feel called upon to produce work that can, at least potentially, benefit all the people of the United States. Beyond that, though, as museum and cultural professionals and human beings, the Web can help us establish and strengthen our personal connection with the human substance and meaning of the collections and programs we present.

Memory, History, Archives and Resources

The partners of ECHO, both as independent cultural institutions and in explicitly collaborative ventures, have created – and continue to create – many kinds and levels of digital or “digitable” content. We have extensive raw video, edited, highly polished video pieces intended for exhibition or educational or cable broadcast settings of performances, interviews and community events. ECHO partners have libraries of raw audio oral histories and language capture, as well as finished audio CDs and commercial-style music and performance recordings Photographic documentation exists in our collections at many levels, including participant snapshots of meetings and events, professional documentation of works of art, commercial-style photography of artists’ production, formal images of cultural venues and portraits, and scans of thousands upon thousands of historical documentary photographs of people, places and things long vanished. Finally, partners have developed educational texts such as lesson plans, curricula, essays, object descriptions and interpretation, classroom activities and discussion questions at many different levels of sophistication and utility, built on many different classroom or free-choice models, comprising everything from didactic wall labels to a full unit covering many weeks of multi-dimensional, interdisciplinary classroom instruction.

The question is what to do with all of it? How should we to use it to reach out to our intended audiences in the most effective way, to have the desired impact, and to learn enough about that impact to be able to improve our offerings and delivery systems? Furthermore, how do we steward these collections of meaning, language, image, object, and ceremony in ways that are both respectful and responsible to the creators and their heirs, and to the heirs of the human story written broadly?

It is a tall order. We have created a variety of sites over the past 5 years to connect to our diverse cultures, communities and histories and make them available through the Web.

Web Projects

Web Projects

Fig 4: The Home Page of the New Trade Winds project http://www.newtradewinds.org/home.html

New Trade Winds (http://www.newtradewinds.org/home.html) was the first Web project to present the ECHO partners as a unified entity. It was an ambitious effort to educate the public about the – surprisingly substantial – historical connections among the three regions. Engaging Web experiences for students and teachers were developed, grounded in (and bounded by) the historical narrative. This site has several technical innovations. There is an interactive timeline marking the separate but intertwined histories of the three regions. There are lesson plans for Elementary, Middle and High school grade bands with linked illustrated stories and correlations with state standards of ECHO home regions.

Fig 5: The Interactive Trade Map on the New Trade Winds project http://newtradewinds.org/kids/index.html

There is a map-based interactive tool that teaches about interactions between regions using historical trade routes, with the objects that were traded, now gathered in our collections, as teaching aids. New Trade Winds is a strong statement of ECHO’s values. It is a highly unusual collaboration between three very different kinds of cultural organization. More to the point, it holds the promise of a new way of looking at history, mindful of and representing multiple viewpoints.

Fig 6: The Massachusetts page on the New Trade Winds Living Artists Gallery http://pem.org/ntw

New Trade Winds Artists Gallery (http://www.pem.org/ntw/), originally planned as a sub-site of New Trade Winds, was very different in conception. It was ECHO’s first site to rely heavily on the community for content, a curated list of links to Native culture bearers, artists, and craftspeople in our communities helping to keep cultural skills and knowledge alive. The site is still up and running as part of Peabody Essex Museum’s Web site. It was our first attempt to provide an output channel to Native communities.

Fig 7: Partners page from Echospace.org http://echospace.org

ECHOspace (http://echospace.org/) was conceived as a catalog of partner media including video, audio, text, photographs, Web sites and collection databases with widely varying standards and formats, produced by the partners both singly and in collaboration. Development of ECHOspace was driven by our desire to showcase the extraordinary range of these materials: New Trade Winds’ profile as an integrated educational site with focused content was too limiting. ECHOspace opens the wealth of our storehouses to a broad public and lets them search and use as they like. Although similar in concept to the New Trade Winds Artists Gallery in its clearinghouse nature and neutral tone, all ECHOspace content was created within the partner institutions rather than out in the community. Over time, it has come to act as a public bulletin board of ECHO projects, including schedules of performances, stand-alone curriculum units, and background material on the partnership.

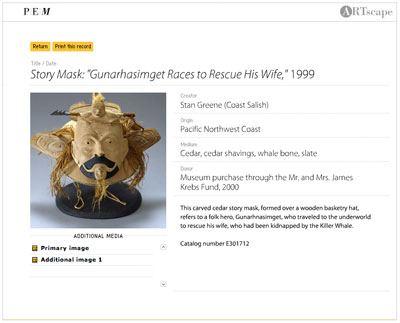

Fig 8: Interface from the Artscape collection database, Peabody Essex Museum http://pem.org/artscape

Artscape (http://pem.org/artscape/) is not, strictly speaking, an ECHO collaboration, in that it was created by a single institution to highlight its own collection. It is nonetheless relevant to the present discussion, since it includes two innovations addressing needs most clearly voiced, in PEM’s experience, by Native museum professionals and communities. First, the structure of the database is open, allowing, for example, for multiple documents, images, audio or video files to be attached to a single object, and allowing for commentary from multiple viewpoints – consulting curators or cultural experts, for example – to be attached to a single object record.

Fig 9: Detail screen from the Artscape collection database, Peabody Essex Museum http://pem.org/artscape

Secondly, the site encourages audiences to interact with content, to participate in their own education by building personal collections within the museum and the site. In its initial realization, the system, for it was more than just a Web site, included the capacity for a live visitor to wander the museum, tagging artworks with their hand-held audioguide wands. After docking the audioguide and entering an e-mail address, the visitor could direct information on the selected works home for future reference. Although the handsets didn’t survive, visitors to the Web site can still select and store a collection of objects to share, revisit, or link to.

Fig 10: The Home Page of the Hawaii Alive project http://hawaiialive.org

Hawai’i Alive (http://hawaiialive.org/), another institution-specific project, was designed by the Peabody Essex Museum under contract to the Bishop Museum with help from WGBH, Boston’s PBS television station. Bishop Museum then contracted Red58 Communications to continue development of the site, bringing it to its current state. Hawai’i Alive represents a fundamentally novel approach to on-line content, providing images, video, historical photographs and educational units and standards through a distinctive cultural lens. The architecture of the site presents all didactic content, including scientific, historical, and cultural material, through three levels corresponding to the traditional Hawaiian spiritual realms: Wao Lani, the heavens; Wao Kanaka, the earth; and Kai Akea, the sea.

Fig 11: Detail Page of the Hawaii Alive project http://hawaiialive.org

Given that the State of Hawai’i educational standards require much of this content to be taught in K-12 classrooms, the site is able to incorporate correlations to Hawai’i state educational standards for every aspect of site content, while presenting a culturally sound perspective on the material. During the development of Hawai’i Alive, focus groups of Native and non-Native Hawaiian teachers were convened. They worked with a prototype and told us how the site responded to actual classroom needs. The project was validated by the teachers, who noted that up to that point there had been no authoritative information on Hawaiian culture on the Web. The Bishop Museum, with the world’s foremost collection of Hawaiian material and traditions, is well positioned to supply that need, formerly met by the community themselves through Wikipedia.

This project also showed us the limitations of expert technical consultants with projects incorporating Native themes and outlook. WGBH provided videography and editing services to the partnership, but the results were mixed. Some material had to be reworked or even abandoned, due to an organizational culture unused to the process of working with Native cultural and, indeed, sacred content. As we have often found in our collaborations, schedules and timelines that do not allow sufficient time for consultation often create rather than solve problems. The assumptions of Euro-American professionals may not correspond to the reality experienced by people in the community, and substantial cultural assimilation and education of the specialists may be necessary.

Fig 12: The Learning From The People project on WGBH's Teachers Domain Web site http://teachersdomain.org/echo

Learning from the People (http://www.teachersdomain.org/echo), our most recent effort, was commissioned from WGBH as a special collection under their classroom resource Web site, Teachers’ Domain. It was created over the course of some eight weeks, and went live in February of 2007. The site is a focused collection of 13 video and interactive resources drawn from ECHO partner raw materials, with background essays, discussion questions and correlation to state standards, all of which are gathered into five lesson plans. It is a focused application designed specifically for use in the classroom.

The process of construction worked well and quickly. WGBH hired editors, writers, content specialists in education, and project management. The ECHO partnership delegated authority for contracts and finance, educational content, and production to three ECHO staffers. Each institution designated a point person to manage the in-house process for approvals and for all other contact with WGBH. As the partners fed content ideas and raw materials to the production team at WGBH, the team fed us back drafts of background essays and lesson plans. While they wrestled with our raw resources, we edited and re-wrote their essays, clarifying meanings or concepts and pointing out areas where they inadvertently veered into a problematic interpretation of a sensitive topic or event.

Since ECHO is literally spread out halfway across the world, the WGBH team posted draft video and interactives on an ftp site for approval. Using Teachers’ Domain guidelines together with ECHO partner content ideas, WGBH created “assets”, in the form of 3-5 minute videos or self-teaching, interactive elements based on 10 to 12 still photographs. They wrote 500-word background essays on each asset, and sets of discussion questions to use with the essays. A single asset, together with its essay and questions, comprises a completed “resource”. Ultimately they created 13 integrated resources and five lesson plans supported and illustrated by those resources at appropriate places.

Fig 13: Resource From The Learning From The People project on WGBH's Teachers Domain Web site http://teachersdomain.org/echo

One of Teachers’ Domain’s most important innovations is the development of a proprietary standards database capable of correlating lesson plans with national and state standards in science and math for the 50 US states. Visitors to the site enter a home address on log-in. WGBH software reads the home state, and generates a real-time set of correlations based on comparison of terms from resource essay texts to a database of state standards.

Our Web sites have ranged up and down the “Knowledge Hierarchy” (Sharma, 2004) from providing access to data for anyone who might want it, to providing detailed interpretation of events and ideas correlated with state frameworks to impart specific knowledge. They have also ranged from simple collections of community member links, to sites on which we created and controlled all content. In planning for a new Web presence for the ECHO project, we hope to come closer than we have in the past to finding a balance among all of these, providing content, but also allowing access for others to develop content as well. We hope to use the authority of our museums, as Australian museologist Tony Bennett proposes in The Birth of the Museum, not so much to “claim…the status of knowledge”, but to become an organization “whose function is to assist groups outside the museum to use its resources to make authored statements within it” (Bennett, 1995: 104), to connect us with our audiences and permit us to work together to tell the stories our collections and communities contain.

Program For A Unified ECHO Voice

To begin to create our new site, we have to understand what we want to get out of it. When we started, we didn’t yet know to whom we were speaking. After five years, much of the guesswork is behind us. We have some history, we can see the shape of the collaboration, and we have greater unity about our ideals, values and goals. We can also begin to imagine and understand our natural audiences, rather than just making a place to hang our stuff.

Goals For A New Site

There are three chief goals for the new site.

1. First, the site should provide a unified voice for the ECHO collaboration. Throughout our projects, both on and off the Web, there are good ideas, materials and resources that we want to use. No single ECHO site captures the range and essence of the partnership. We hope to facilitate new discoveries and uses of our collections by bringing our resources under one roof. Previous ECHO sites have been created as discrete entities, focused and bounded by their initial concept. This site should be able to grow, to expand as people use it, it should be accessible to our Web developers and museum staff, to change and update as necessary, and it should be capable of absorbing what we create together. We have certain content pieces (the 13 resources and 5 lesson plans from Learning from the People, the map and timeline interactives from New Trade Winds, and many lessons and resources on Hawai’i Alive, for example) that do not yet coexist. We need to construct an architecture defined by a set of ideas that can be populated by what we have already, and what we create in collaboration with our communities. In essence, this reconstruction project is about organization and structure rather than content.

Fig 14: User Matrix schematic for the echospace.org redesign

But there are other constituencies than ourselves.

2. The second goal for the site is to reach into our communities, not only to teach, but also to provide them with tools to express themselves directly, to participate with us in creating the content of the site. We understand that the major audiences of ECHO are K-12 teachers and their students; parents and children; Native communities; museum audiences/lifelong learners; and culturally inquisitive young adults. Having identified these audience groups permits us to envision the capabilities they need, based on the experience of our collective institutions. It also permits us to conceive the site to respond to their wishes and to offer them tools they will use. Characteristics of these groups define the capacities we have to build and the pathways we can use to approach them. Ultimately it is a matter of approaching them as equals and listening to what they tell us.

Through our experiences within the partnership we have learned that to engage communities successfully we must respect their traditions, integrity, and values. Communities may not be willing to settle for externally produced information - such as lesson plans and videos – because of the values and assumptions that come with them. To reach and effectively serve such communities, it may be more important to provide tools than knowledge, because knowledge originating outside the community is necessarily filtered through outsiders’ cultural assumptions.

Museums, in general, share relatively few characteristics with Native communities. One of those shared characteristics, though, is an attachment – a commitment – to “place” and its corollary “presence”. Many consider that teaching through the application of Native knowledge, and place – and culture-based education, keep Native students involved with school longer and produce better outcomes. That is justification enough to create tools to teach in that mode. It is our intuition, though, that if we provide or enable others to create lessons based in locales such as museum collections and Native traditional communities, they will be meaningful – to say nothing of exciting – not only to the students in those locales, but also to many kinds of students in many parts of the country.

It is our assertion in the design of this site that teachers, students and parents will find value in the expression of local and communal values and stories, that State and Federal curriculum standards are a fact of life, but that those standards can provide a common set of ideas and facts with which to negotiate the wider world if they can be integrated with the language of the community. It is also our expectation that, if we build a set of capabilities and opportunities, we will be able to observe how the tools are used and adapt and improve the offerings as we learn more about our audiences.

A main concern, then – if community participation in content development is to be central – is access. The new ECHO site should be easy to understand and use, should allow visitors to store self-generated content of a variety of types, and should protect intellectual property rights of both content creators and those who use content to learn and to teach.

Tony Bennett observes that museums currently feel themselves torn between the entertainment and educational industries, towards both of which the visitor is essentially passive. He supposes the public has a “right to make active use of museum resources rather than an entitlement to be either entertained or instructed” (Bennett 1995: 105).

3. The third goal of the site, based on our responsibilities as federal grant recipients, museum professionals and human beings, is to produce a site that is applicable across the country. None of the audiences we seek are defined by geography, so our efforts to serve our audience should be as broad as possible.

In order to be nationally relevant, we have to make the site searchable, usable on a wide variety of machines, and easy to use with little training; we must pay attention, after it is launched, to linking with other sites, notifying bloggers in the education space, and generally marketing the site to the audiences we seek. By working with our partners at the Dept of Education, we can find many outlets within Native American educational communities. Using a combination of direct outreach to visitors, development of links with targeted teacher and cultural Web sites, a PR push to bloggers with interests similar to ours, purchase of a limited selection of search words on the major engines, and presentations and workshops such as this one, we will spread the information sufficiently widely to begin to see visitor-to-visitor communication picking up and propelling us into communities where we do not have other access.

Of the tasks required for national relevance, making the site searchable raises issues that are politically and technically complicated. Our experience with teachers showed that they searched for classroom resources in ways we did not expect. The anecdotal evidence given us by the Hawaiian focus groups, among others, indicates that teachers only rarely download and use complete lesson plans. Instead, they use plans as keyword clouds to build queries that give them results that include the sites they want. This tells us we should treat all the text on the site as keyword clouds, and possibly (if the observation proves to be generalizable) rely less on lesson plans and more on tagging as a way to communicate content to visitors.

Another aspect of the complexity of searching involves the 50 state and national educational curriculum standards. In addition to searching by lesson plan words, teachers tell us they frequently search for classroom resources through querying the actual standards they have to fulfill. The imposition of state standards in education is controversial. Native, poor, and otherwise underserved populations have suffered, in relative terms, under centrally imposed concepts of knowledge. Educational strategies that acknowledge and celebrate diverse models of learning are at a disadvantage in the present system. The potential of standards, though, lies in the fact of their universality: almost all teachers have had to learn them, and, as such, they begin to provide a “universal language.” If we can provide tools to create lessons locally, then post them on the Web correlated with the 50 state standards, teachers all over the country will be able to search quickly and easily among lessons that may incorporate local knowledge that, while far from their locus, may well resonate with and influence the behavior of their students.

Teachers’ Domain’s database system works well for the science and math standards, for which GBH has built complete databases, but is not (yet) effective in the Social Studies or Language and Literacy disciplines, which, of course, are central to our efforts. Since it is proprietary, it is not possible to migrate the correlations along with the resources and lesson plans. There are other vendors, however, who can provide correlations.

Teachers’ Domain is not owned by ECHO. This makes it difficult for us to link these resources to other potentially valuable partners such as NEH’s EdSiteMent teacher Web site, a resource that is focused on, and heavily used in, the disciplines of Culture, Arts, History and Language & Literacy. While Teachers’ Domain is fairly widely used, its specialty lies in the sciences. We need to be able to share our site easily with other providers, and we need a cultural context.

How To Realize Those Goals

Fig 15: Site Architecture schematic for the echospace.org redesign

The approach we have chosen to achieve these goals is to incorporate our partner material as a kind of example, or “style guide”, to seed the culture of the site. To this material we will add open source and free Web applications which we will continue to incorporate and update as they develop and improve. This combination will enable our community collaborators to develop, store and index their own materials, drawing on our examples to the extent they are useful. We are making an assumption that providing access to tools and information about how to use them is as valuable as providing finished materials, in accomplishing the cultural and educational goals of the site. By making high quality technology available and easy to use, we can encourage people to develop their own culturally-based educational materials, tailored to their situation but applicable across the country. It is inevitable, if they achieve that much, that they will be resourceful and engaged citizens of the Web.

Fig 16: Site Architecture schematic for the echospace.org redesign

The proposed structure of ECHO’s new site is outlined on the attached illustration. The main page will identify the partners and the project, and offer access to several kinds of experience, here titled ECHO, Classroom, Share, and Tools & Materials.

ECHO will contain a variety of content elements describing the program, the partners and the partner regions. It will incorporate a map of the partners, to which visitors can add their own locations. It will include a sub-site illustrating and describing the kinds of cultural transformation we aim for: a young man’s photograph with a bowl from our collection that changed his life, with his narrative; another with audio from a grandmother and grandson telling a story. It will also provide a textual and photographic document of the nature, character and accomplishments of ECHO.

Classroom will incorporate finished ECHO lesson plans with links to video, audio, interactive and text resources, along with correlations to the state and national educational standards. The lesson plans will be grade banded and relatively brief, encompassing not more than 5 class meetings. Each resource will have a media component, a background essay and discussion questions. The media components will be approximately 3-5 minutes long, the essays not more than 500 words.

Share is a space for community members. They can create a virtual classroom to post students’ work, they can post their own lesson plans to share among themselves, there will be chat space available which may ultimately develop into several distinct spaces (for teachers, Native communities, home schoolers, etc.), and, in time, a series of themed blogs by leaders in the various communities of which ECHO is a part: Native education, cultural knowledge, education policy, Native arts, and others.

Tools & Materials will be the media database capable of indexing images, text, video, audio, and Web tools to manipulate and store them, and to link them with the lesson plans on Classroom and Share. The database will be a series of links out to public media storage and retrieval sites such as Flick-r, YouTube, or i-Tunes, as well as textual descriptions and correlations to state standards. It will also incorporate text, video and interactive instructional materials showing how to store, access and use elements on the site, including suggestions derived from ECHO experience on creating successful resources for the site.

In addition to these major sub-sites, each page of the site will incorporate a set of footer links to communicate with ECHO, to navigate the site, and to tag site elements with user tags, allowing users to create their own navigation and retrieval systems.

Incorporating communities in the site is a commitment. It not only requires keeping the site constantly updated and monitored, but also requires a robust program evaluation and improvement scheme. We will build in a series of evaluation tools based on identified goals for the project, as well as Web site statistics of visitation and usage. These tools will include an avatar or game style interface that will appear at specific locations to inquire about visitor experience and an e-mail survey using addresses provided at log-in (required for up- or down-loads).

Conclusion

ECHO is a partnership spread across continents and oceans, but the most significant yet rewarding distances we travel as we meet and plan programs and projects are those across cultures. Museums are often in the position of representing cultures they may not, within their own staffs, share. In this partnership, and from the perspective of Peabody Essex Museum, we have the luxury of knowing the people whose works we steward. We can build on these relationships to wrap the objects in our collections in a mantle of context, spirit and meaning. As we move forward with the re-construction of our main Web presence, our partnerships with Native people and communities bring our efforts down to earth. In however a fragmentary and limited way, we have devised this site in communication with those who will use it.

We were faced with several challenges, common to most museum sites. Who is our core audience? What boundaries can circumscribe the content we provide so as not to overtax our productive capacity? (We cannot, for example, digitize and present the 800,000+ objects in Peabody Essex Museum’s collections.) How can we evaluate our efforts effectively to help us improve their focus? What do we do with the hundreds of hours of videotape, thousands of digital photographs, and dozens of curriculum units, lesson plans, and activities we have generated over time? Most importantly, perhaps, what can we do that will be of the greatest benefit to the greatest number of the members of our audience, on whom we place the highest priority? There are a string of judgments called for here, establishing hierarchies of benefits, and audiences, and quality of impact or access. To make those judgments carefully, in full collaboration with the communities we seek to serve, will require deftness, balance, sensitivity and good ears. Without shared value systems, little can be accomplished. The task is to agree upon the values that drive us, the audiences we serve, and the tools we possess to move them. The challenge, posed by Bennett, is to get the levers of the museum machinery into the hands of those whose cultures we have guarded so jealously.

References

Bennett, Tony. The Birth of the Museum: History, Theory, Politics. Routledge, London & NY, 1995.

Sharma, N. Origin of the Data Information Knowledge Wisdom Hierarchy, 11/01/2004, http://go.webassistant.com/wa/upload/users/u1000057/webpage_10248.html; accessed: 8/31/2007, quoting Cleveland, H. “Information as a Resource,” The Futurist. Washington: Dec 1982. Vol. 16, Iss. 6; pg. 34, 6 pgs.