Introduction

The Royal Observatory’s Astronomy Photographer of the Year was launched in January 2009 as part of the International Year of Astronomy celebrations. It’s an annual competition and exhibition for everyone who loves the night sky, from young photographers to professionals.

The competition-and-exhibition format was inspired by the London Natural History Museum’s successful Wildlife Photographer of the Year programme ,and the project concept developed as a media partnership with BBC Sky at Night magazine.

This paper explores the journey from fairly traditional format idea to final product, and its transformation using Flickr as a digital platform – an approach that enabled us to reach new and international audiences, harness innovative astronomy technology, and link on-line and exhibition visitors, all on a shoestring budget.

Building the Case for Digital Outreach

Astronomy Photographer of the Year started as a relatively straightforward exhibition project with a print-media partnership. There wasn’t a budget for an accompanying Web offer. However, there was a strong case for the project being digital-led.

First, there was a huge opportunity to broaden participation: astronomy photography has a massive on-line following, with over one million daily visits to NASA’s Astronomy Picture of the Day Web site (http://apod.nasa.gov/apod/). It’s not just preaching to the converted, either. Beautiful photography is one of the three main drivers of casual astronomy interest, alongside astronomical events and news of discoveries. Second, most astrophotographs are ‘born digital’ – submissions really should be on-line. The question was, ‘How can we do this with no money and convince everyone it’s a good idea?’

The museum already had a profile on Flickr (http://www.flickr.com/nationalmaritimemuseum), was a contributor to The Commons (http://www.flickr.com/commons), and hosted public Flickr Groups – such as Beside the Seaside (http://www.flickr.com/groups/besidetheseaside/) and Sailor Chic (http://www.flickr.com/groups/sailorchic). But these initiatives had been developed independently by the digital media department. Astronomy Photographer of the Year was a cross-departmental initiative, and we therefore needed to persuade others of the benefits of digital outreach on non-museum platforms.

Why Flickr?

‘A great place to be a photo’ (Bob Baxley, via George Oates, 2008).

We proposed Flickr as the best platform for an on-line photography competition on the basis of its reach, appropriateness and flexibility:

- Reach - At the time, Flickr had over 40 million unique visitors each month and 2.4 billion photos, with almost three million photos uploaded every day. It was available in eight languages.

- Appropriateness - ‘Almost certainly the world’s best photo-sharing Web site,’ Flickr is designed specifically to showcase digital (or digitised) photography. It has an active, engaged community with a deep connection to photography. Astrophotography was already well represented. An informal review of Flickr at the time showed that there were 8,522 photos clearly identified as ‘astrophotography’ (Fig 1) and 32,281 tagged as ‘astronomy’. And simply retrieving the five most ‘interesting’ astrophotography pictures on Flickr demonstrated remarkable quality.

Fig 1: Flickr photographs tagged with ‘astrophotography’, ordered by interestingness (http://www.flickr.com/search/?q=astrophotography&s=int, accessed on 31 January 2010)

- Flexibility - Flickr had a mature and relatively well-documented Application Programming Interface (API) which would enable the museum to integrate the Flickr group with the museum’s Web site, develop a sophisticated competition administration tool, and produce interactive exhibits.

Tate Britain had already set a precedent with its well-executed photography competition How We Are Now, which attracted over 3,000 members and 6,000 entries via Flickr. And we knew from our experience of working with Flickr staff George Oates and Fiona Miller that the organisation was actively engaged with our sector.

As the final argument, we prepared a PowerPoint step-by-step demo of the administration of a Flickr group – group rules, moderation tools and discussions. In the end, it was the sophistication of Flickr’s community and administration features that clinched it.

Flickr groups are now a well-established museum outreach genre, with increasing influence on the host organisation.

Constraints of Flickr

The Flickr platform did present some issues for us to work through.

- Young photographers - The Astronomy Photographer of the Year competition has a ‘Young Photographer’ category for under-16s. Flickr’s terms of service specify an age requirement of 13 years or older. Our ‘Young Photographer’ category was therefore managed independently of Flickr.

- Flickr is also very clear that it is not a host for competitions. It was therefore very important that we maintain a distinction between our community on Flickr and the competition entry process on our own Web site. The museum Web site uses the Flickr API to pull through pictures so participants can enter their top five photos into the competition – this is where we’re picky about rules and how many photos people enter. But in the Flickr group, participants can add more photos than they want to enter in the competition – or choose not to enter at all. And our group stays open from year to year, while the competition has an annual opening and closing date.

- Finally, the terms of use for the Flickr API and Non-Profit groups only allow us to redisplay photographs on our Web site or on-gallery if they remain in the group. Our Flickr-based interactive exhibit therefore needed to connect to the Internet to update its index of photographs every day.

Flickr as a Platform for Technological Innovation

Selecting Flickr immediately got us to ask, what would be the space equivalent of Flickr’s geotagging? Geotagging is the act of assigning geographic metadata to a photograph using the special three-part format of a machine tag (namespace, predicate and value). More than that, it’s a movement to map people’s experiences to location – and it’s something that happens to one in every 30 photos that get uploaded to Flickr.

Could we put space photos on a sky map in a similar way… and could we make it easy and rewarding, just like geotagging? Our answer took a little time to evolve, but ‘astrotagging’ has provided us with not only a contemporary link to Greenwich’s scientific history, but also a means to extend science learning and create novel exhibits and planetarium shows.

Astrotagging – a some-human, some robot approach

Like geotags, astrotags use the three-part machine tag format, in this case the astro: namespace. But unlike geotags, astrotags describe a photo’s celestial subject as well as its location (Fig 2).

Fig 2: The astrotag: a short film about how astrotags work (http://www.vimeo.com/6469344)

The astrotags we’ve defined so far are:

| Astrotags | |

|---|---|

| astro:pixelScale= | Describes how much of space each pixel in a digital photo shows |

| astro:RA= | Measures the right ascension of the centre of a photo. Right ascension (RA) is the space equivalent of Earth’s longitude. It measures how far east or west something in space is along the celestial equator |

| astro:Dec= | Measures the declination of the centre of a photo. Declination is the space equivalent of Earth’s latitude. It measures how far north (+) or south (-) something is of the celestial equator |

| astro:name= | Simply the name of an object in a photo. There can be many objects in each photo |

| astro:orientation= | Describes which way up a photo is, in relation to the celestial north pole |

| astro:fieldSize= | Measures how much space an entire photo shows |

| astro:gmt=yyyy-mm-ddThh:mm | The exact date and time the photo was taken, in Greenwich Mean Time (of course!). yyyy is the year, mm is the month, dd is the day, hh is the hour (using the 24 hour clock), and mm is minutes. T separates the date from the time. For a long-exposure photograph, just the start time is used |

| astro:subject= | Describes the main astronomical subject of the photo, using its English name or letter and number combination. There should only be one per photo |

The extra complexities of astrotagging mean it's not as immediately user-friendly as geotagging. Would anyone really go to the trouble of figuring out and tagging all of that information? And what about fast-moving objects such as comets or planets that have no fixed location?

This might have been an insurmountable barrier. However, the Flickr development team pointed us towards the first part of our solution: the Astrometry robot.

A robot (or ‘bot’) on Flickr is software built on top of the API that acts autonomously for a user or a group. Other bots in use on Flickr include Hipbot and HAL. Hipbot (http://www.flickr.com/people/hipbot) was created by Flickr member jbum to automate some of the moderation tasks in the well-defined squared circle group (http://www.flickr.com/groups/circle/). Hipbot automatically removes photos that are over three per cent out of square, or which are less than 500x500 pixels in size. When the robot removes photos from the group, it tags them as hipbot:unsquare or hipbot:toosmall, or both, providing useful feedback to the contributor. HAL (http://www.flickr.com/people/utatabot/) was created by Flickr member dopiaza to enforce the rules of the large Utata community (http://www.utata.org/). It posts a comment to the contributor:

Hi, I’m HAL the UtataBot. I’m afraid I’ve had to remove your photo from the Utata Pool as it broke one or more of our group pool rules: Your photo was in too many pools (9). Please read the rules for posting to the Utata pool in the group description. (HAL the UtataBot)

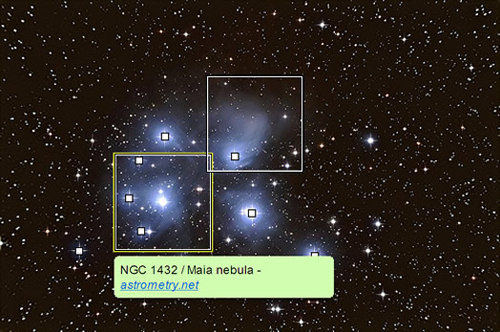

The scientists at Astrometry.net (http://www.astrometry.net/) had already created a bot to solve the astrometry of Flickr photos, adding the results as notes and comments (Fig 3). Adding our defined machine tags too seemed possible – and the Astrometry.net scientists agreed, making a custom robot for our competition’s Flickr group.

Fig 3: Illustration of astrotagged Maia nebula, adapted from a photograph by johnny9s, http://www.flickr.com/photos/johnny9s/2897062004/in/pool-astrometry (some rights reserved, http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/deed.en_GB)

Now, our Astrometry robot goes through all the new photos in the group, posting tags to all successful solves (Fig 4).

| Big Andromeda galaxy (M31) by xamad | |

|---|---|

|

Fig 4: Big Andromeda galaxy (M31) |

astro:RA=10.7496213088 |

Clever as it is though, the Astrometry bot can’t solve every astronomy photo. Because the robot uses the relatively-fixed geometry of stars to calculate what's in a picture (here’s the science: http://www.nmm.ac.uk/visit/exhibitions/astronomy-photographer-of-the-year/astro-robot/), it isn't able to label planets, moons, or other moving subjects such as comets. For example, the Astrometry bot didn’t see Comet Homes in this photo (Fig5), even though it’s the main subject and clearly remarkable to the human eye.

Fig 5: Photograph by paranoidroid, Comet Holmes 11/20, http://www.flickr.com/photos/paranoidroid/2051341577/ (some rights reserved, http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/deed.en)

However, we eventually decided that humans are pretty good at this stuff. Even if people can’t give a precise location as the robot can, they can tag obvious subjects and the time a photo is taken. From this information, it’s possible to place a photo approximately on the night sky.

The point of astrotagging

What can we do with these tags?

astro:RAandastro:Deccontain the right ascension and declination of the centre of the photo. Right ascension and declination give us the position of a photo as a point on the celestial sphere. We can then map our photos and group them by proximity to each other, just as we already do with geocoded photos of places on the Earth.astro:fieldSizetells us the angular extent of a photo on the sky. Similarly,astro:pixelScalegives us the angular size of a single pixel in the original, full-size image.Astro:orientationtells us the orientation of a photo with respect to celestial north. Knowing the position, extent and orientation of a picture, we can overlay it on a map of the sky. One possible application of this information might be to overlay and mosaic photos of the same region of the sky. Another application would be to zoom in and out of a region by comparing photos at the same location but with higher and lower fields of view.astro:nametags a photo with the names or catalogue designations of objects in the field of view. So we could find all photos of the Orion Nebula (NGC1976), for example, by searching for the tagastro:name=NGC1976. Since the names follow systematic, regular patterns it ought to be possible to go further and find all photos of objects in the New General Catalogue (astro:name=NGC*) or all photos of stars (astro:name=thestar*).

Ultimately, for the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, astrotags should enable us to mesh contributed photographs into a beautiful and accurate people’s map of the sky. A very early prototype in Google Sky is available in our showcase (http://www.nmm.ac.uk/visit/exhibitions /astronomy-photographer-of-the-year/showcase/). Astrotags are also compatible with our planetarium software, so we’re aiming for full-dome fly-throughs using our visitors’ own photos.

But there’s another dimension. Astronomical images provoke an aesthetic response (Fig6) that helps engage a variety of audiences (Wyatt, 2008).

The Hubble images are part of the Romantic landscape tradition – they fit that popular, familiar model of what the natural world should look like. (Elizabeth Kessler in Carnig, 2005)

Fig 6: Astronomy Photographer of the Year, competition winner, Horsehead Nebula, by Martin Pugh (http://www.flickr.com/photos/36418300@N02/3362016992/, all rights reserved)

New (preliminary) results from a study of NASA’s Astronomy Picture of the Day Web site suggest that people find astronomical pictures more attractive if they’re given more information about them: “Once [people] know what the image is about, they find the image itself better, more interesting, and more attractive” (Smith, 2009) .

This suggests that the addition of astrotags might not only increase the scientific information and potential for learning, but also motivate deeper engagement with the images and a heightened aesthetic pleasure in them. An anecdotal survey of comments on photos in our Flickr group seems to support this idea:

“Galactic dust? Who knew it could be so spectacular!”

loveMER on Martin Pugh’s highly-commended image of Galactic Dust in Corona Australia

“This is amazing. I never imagined the Milky Way to be like this! It’s breathtaking.

Vi P on Nik Szymanek’s highly-commended Milky Way

Much of the pleasure here seems to come from disrupted expectations. This is something we hope to research further.

Astrotagging in historical context: sky maps at the Royal Observatory

Astrotagging is the latest aspect of the Royal Observatory’s historic and continuing role as the home of human measurement of space and time.

Founded in 1675, the Royal Observatory, Greenwich is home of Greenwich Mean Time and the Prime Meridian and one of the most important historic scientific sites in the world. The Royal Observatory’s historic South Wing (Fig7) – site of the Astronomy Photographer of the Year exhibition – was actually built for astrophotographic work, under the guidance of Astronomer Royal Sir William Christie.

Fig 7: In the foreground, the astrographic dome at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich

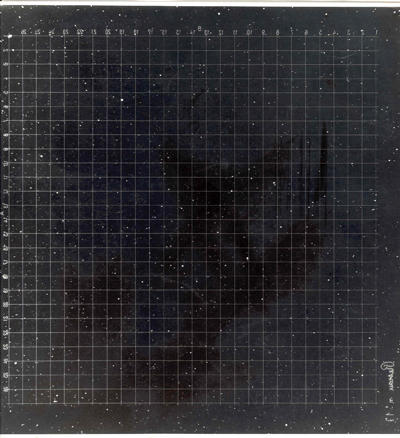

Following a meeting at the Paris Observatory in 1887, scientists from 18 observatories around the world embarked on an ambitious new project, Carte du ciel. Their aim was to use new photographic technology to make a huge map of the stars – larger and more detailed than any before it.

Each observatory installed a standardised astrographic telescope and was allocated a section of sky. It then began to produce photographic plates to agreed exposures and magnifications (Fig8).

Fig 8: One of the astrographic plates produced during the Carte du Ciel project

At the Royal Observatory, Sir William Christie founded a new research group to take on this endeavour, the Astrographic Chart department. Their new instrument, a 13-inch refractor made by Sir Howard Grubb of Dublin, was mounted in the Astrographic Dome in 1890, where it remained until 1957.

Greenwich was responsible for taking over 3000 plates. It was a huge task, and one that had been underestimated. Christie had thought the project would be complete in 10 years, but by 1909 the Royal Observatory was the only one of the participating observatories to have completed and published its work.

In fact, complete sky charts for the Carte du Ciel project were never assembled. So it seems apt that today, the Royal Observatory’s visitors can pick things up using astrotags.

Evaluating Astronomy Photographer of the Year 2009: What Worked and What Didn’t

Following the 2009 competition, we wanted to take stock. We started with a thorough assessment of our group – taking a quantitative approach using Flickr tracking tools (http://dev.nitens.org/flickr/group_trackr.php) and a qualitative one by looking in detail at the interactions that had gone on over the year. We also analysed our museum Web site traffic using Google Analytics, and reported on other Web, broadcast and print media coverage. This enabled us to compare channels and to assess the extent of our reach in terms of demographics and interests.

Findings

With over 1,000 members, Astronomy Photographer of the Year is a large group compared with the average, but a third of the size of the largest astronomy group on Flickr (http://www.flickr.com/groups/astronomy/), so it could be developed further.

Astronomy Photographer of the Year is an international competition, so we were pleased that entrants represented over 30 countries. Given that print marketing of the competition had really only been distributed in the UK and US, this could be directly attributed to running the competition on Flickr and to coverage from blogs such as the Spanish-language technology site alt1040.com (http://alt1040.com/).

In terms of the annual cycle, the longer the competition goes on, the less traffic it gets, until the announcement of winners approaches. We see a big increase in Web traffic when the winners are announced, with over 70 per cent of visitors arriving through referring sites, especially blogs such as Daily Kos (http://www.dailykos.com/), kottke.org (http://kottke.org/) and the Flickr blog (http://blog.flickr.net/en). The effect of print media was noticeably amplified via Twitter.

The average number of photos posted was low at two per person, considering that members can upload five per month.

Further analysis showed that our group was male dominated – not surprising as astrophotography is too. However, the photos and stories surrounding the photographs had very broad appeal, as demonstrated by widespread press coverage, including in the UK’s biggest-selling newspaper, The Sun.

We also noticed a significant difference between the type of photographs given awards by the judging panel and those picked up by the press before the announcement of winners. In particular, the press ran with photographs featuring people.

Another interesting finding was that although deep space, lunar and landscape photography were well represented, planetary photography was not. Follow-up interviews with planetary photographers suggested that this might be because this is a specialist branch of astrophotography, and its community tends to congregate through clubs and forums. This suggested we’d have to reach beyond Flickr to recruit these photographers.

Sustaining the community

When we first started this project, we wanted to make sure that the digital outreach we achieved built year-to-year. There was potential tension in the way our group was established: people need an incentive to join and actively contribute, and a competition can provide this. But competitiveness can be the antithesis of community spirit.

However, the competition did not overwhelm the community. In fact, not all group members entered the competition, and many members continued to submit photos to the group even after the 2009 results were announced, showing that they valued the group as a space to share expertise.

Affinity space

Flickr can be understood as what James Gee termed an ‘affinity space’, a place characterised by the sharing of knowledge and expertise, and sustained by common endeavour (Jenkins, 2006).

Experienced photographers in the group enjoy informed feedback from their peers, such as the following comments on Ethan Allen’s highly-commended image of Saturn (http://www.flickr.com/photos/96552810@N00/3138962663/): “an amazing image, well worth the hours of exposure” and “excellent Saturn image Ethan = great work on colours and rings!”

Those who are less experienced, or don’t have the same physical or technological access, are inspired by the work of others:

I thought you could only get these sort of deep-space shots from things like the Hubble. I could just sit and meditate on them for hours. (catherineforbes on competition winner, Martin Pugh’s Horsehead Nebula) (http://www.flickr.com/photos/36418300@N02/3362016992/)

That is amazing. I would love to do this kind of a shot some day. Yours turned out fantastic. (Pinkrinkydink on Nikhil Shahi’s highly-commended Death Valley Star Trails) (http://www.flickr.com/photos/21658243@N03/3159972600/)

A fantastic image of a fascinating object. Beautifully captured and processed. Another southern object I would love to see. (beyondvision2009 on highly-commended Michael Sidonio’s Centaurus-A: Ultra-Deep Field) (http://www.flickr.com/photos/62246125@N00/3511710813/)

Most photographers in the Astronomy Photographer of the Year group write detailed descriptions of their process and equipment, and the swapping of tips in comments appears to be a powerful motivator. For example, in the description for M33 v2 DDP crop (http://www.flickr.com/photos/31986095@N05/3995061414/in/pool-astrophoto), eriknlarsen says:

I did frame it badly and so I had to turn it 90 degrees and then crop it, that makes for kind of a tight FOV but luckily I think the data is good enough that it held up.

Im still not sure about the color, ive been looking at this too long during processing so tell me what you think.

32 5min subs ISO 800 stacked in DSS then adjusted in PS CS2 with a large crop. Canon 400D(modded), Orion Atlas mount and the scope is a Celestron 8" SCT with a .63 focal reducer(FL 1280) and a Orion ED80 refractor as a guide scope.

In addition to posting reassuring feedback on his image (“Fantastic, as always”), eriknlarsen’s followers provide detailed advice:

Looks great to me...maybe a tad shy on data on scrutiny...aren't we all...?

Sounds like you need an arborist to trim some trees !

color looks good to me...

I have yet to try it @ 1260mm...(f/6.4)....

where was histogram on camera ? (dave halliday)

A lot of details and nice H-alpha regions inside of M33. I downloaded your large sized photo and opened in PS CS2, went to AUTOCOLOR since I noticed a bit more blue in WB. Autocolor really improved histogram which is now equal for R G & B.

Very nice, I hope I'll could make as good as yours soon. (gucic)

Further examples of photographers sharing detailed descriptions of their capture and processing methods can be seen on Milky Way mosaic (http://www.flickr.com/photos /31986095@N05/3010982471/in/pool-astrophoto), Whiling Away Half an Hour at Pfeiffer (http://www.flickr.com/photos/steventheamusing/4294831636/in/pool-astrophoto), and 0 3 09 solar prominence crop (http://www.flickr.com/photos/23953201@N07/3996465190/in/pool-astrophoto).

Unsurprisingly then, of the discussions that we initiated, those asking for members’ tips got the best responses; for example, a call for advice to young photographers (http://www.flickr.com/groups/astrophoto/discuss/72157613158337566/) and a question about how to make a barn door tracker (http://www.flickr.com/groups/astrophoto/discuss /72157613462993422/).

Some of our group members already have strong connections and follow each other’s work with great interest, as demonstrated by this comment (http://www.flickr.com/photos /31986095@N05/4107767871/#comment72157622838110914) from jasmel90:

Dude! the work You, DangerousDave, and Eriknlarsen have been doing lately is amazing! you guys are making me re-think posting any of my DSO work! this is great! (jasmel90)

Affiliation

The competition’s association with the Royal Observatory, Greenwich – and the chance to be exhibited there – was an important factor in Flickr members participating in this particular astrophotography group.

Having a physical manifestation of the group itself went down well too – both in terms of the interactive display (Fig. 9), which featured every photo shared in the group, and the use of members’ comments on the exhibition labels, alongside those of the competition judges.

Fig 9: Photograph of Astronomy Photographer of the Year interactive, by eatyourgreens (http://www.flickr.com/photos/eatyourgreens/4038471956, some rights reserved, http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/deed.en_GB)

One member contacted via Flickr mail for permission to display a comment replied:

I’m honoured that you’d want to use my comment in your exhibition… Please feel free to use it!

This suggests that institutional affiliation with the Royal Observatory encourages participation in the group and echoes initial findings that institutional affiliation can motivate participation for the art museum social tagging project, steve (http://steve.museum/) (Trant, 2009).

As you’ll see in our 2010 developments, we’re building a bigger and more sustained on-site presence for the competition. We’ve also proposed that the museum collect the winning Astronomy Photographer of the Year images as one of its first ‘born digital’ acquisitions.

The bargain

Organisations like museums have to come to grips with what they are willing and able to offer to support and sustain participation. As the name ‘bargain’ suggests, it’s all about negotiation.

(Russo and Peacock 2009)

Given our aspiration to sustain the community year-to-year, it was essential that we respond to our community’s feedback about how the competition and group should develop. Some of the liveliest discussions in our group have been disputes about the competition rules:

- Our competition rules allow the use of robotic telescopes (http://www.flickr.com /groups/astrophoto/discuss/72157615804347137/). While we assured our Group members that the judges would take capture methods into account, there was still concern that the use of robotic telescopes would give some entrants an unfair advantage. This led to suggestions for categories that were tied to the level of equipment used.

- Our competition rules don’t allow collaboration (http://www.flickr.com/groups/astrophoto/ discuss/72157615804347137/). However, it is common in this community for one person to capture an image and another to process it.

And since the launch of the 2010 competition in January, a discussion has already started about the rule around pre-publication (http://www.flickr.com/groups/astrophoto/ discuss/72157623286308466/). This rule was clarified in response to questions last year. There’s a clear tension here between the photographers’ interest in getting exposure for their work, and the museum’s desire to secure press coverage for the winning photographs – it’s a difficult one to resolve.

The 2009 winners were generally well received, but there were a couple of concerns about the selection:

- There was some discussion in the Flickr group about the dominance of English-language countries (http://www.flickr.com/groups/astrophoto/ discuss/72157622346480806/). Google Analytics shows that most visitors to museum’s Web site were from the USA and the UK, although there was a strong representation of visitors from Italy, Canada and Australia.

- There was also a sense that most of the adult winners had used very expensive equipment: “Wow, to paraphrase Jaws, ‘I’m gonna need a bigger telescope’.” responded markkilner. It would be a shame if this perceived expense deterred other entrants because equipment is certainly not the only predictor of photographic quality.

I have been interested in astronomy since about the age of eight or nine. My interest in astrophotography was fuelled by the ‘Webcam revolution’. The use of these cheap devices along with modern digital image processing has enabled amateurs to produce amazing results from relatively modest equipment. (Nick Smith, runner-up in the Our Solar System category)

In our more contentious group discussions, we’ve noticed the emergence of community leaders who try to moderate the conversation. And we’ve tried, as far as possible, to respond to the feedback.

Audience Aims for Astronomy Photographer of the Year 2010

Our analysis of the 2009 Astronomy Photographer of the Year competition and community pointed towards the following aims for 2010:

- increase entries from 500 to 1000

- extend reach to international audiences

- extend reach to planetary photographers

- encourage women and girls to take up astrophotography

To achieve these aims, we have already made a few changes.

Judging panel

We have invited more women with astronomy or photography expertise to sit on our judging panel – it’s important that we represent women as part of the project if we want more of them to join in. Joining Rebekah Higgitt (Curator of History of Science and Technology) on the judging panel, we have Olivia Johnson (Astronomy Programmes Manager), and Melanie Grant (Picture Editor on Intelligent Life Magazine at The Economist).

Special prizes

We’ve also been thinking hard about ways to encourage new members: capitalising on the beauty and broad appeal of the photos themselves while providing an easy way to get started. We hope that two special new prizes this year will respond to concern about the cost of equipment needed for deep space photography. One prize is for newcomers to astrophotography, and another is for pictures featuring people. The idea is that these will appeal to creative types, who have a DSLR but not necessarily a telescope.

Screenings at the Planetarium

What also became clear last year was that we needed a range of incentives for people to take part. The competition was a great incentive for some, but it did change the community dynamic. The popularity of an Astronomy Photographer of the Year planetarium short at the awards ceremony (http://www.flickr.com/groups/astrophoto/discuss/72157622197477165/) inspired us to project members’ galleries on the dome in a monthly planetarium short.

Guest-curated galleries

To build extra interest, we’ve invited professional astronomers to join the group and curate their own galleries from the pool. Among them will be non-UK and US astronomers and women – so addressing both our aims on these fronts. We hope that from now until the competition closes there will be a new ‘guest-curated’ gallery every month. The astronomers that produce them will also be invited to contribute to discussions about the science behind the pictures they’ve chosen, and about their professional work. We think this will complement the active discussions about how to photograph astronomical subjects, and encourage members to create their own Astronomy Photographer of the Year galleries.

Events at the museum

Finally, we’ve programmed ‘Snapping the sky’ astrophotography workshops at the Royal Observatory to help develop new talent.

Developing Astrotagging

We’re also keen to continue developing our astrotagging standard. In particular, we’re interested in Flickr’s machine tag ‘extras’: the process of using a machine tag as a key to access data stored on another Web site. To date, Flickr has made them available for Upcoming (http://upcoming.yahoo.com/), Last.fm (http://www.last.fm/), Dopplr (http://www.dopplr.com/), Open Plaques (http://www.openplaques.org/), Open Library (http://openlibrary.org/) and Noticings (http://noticin.gs/). A machine tag extra for astrotags could link objects to a catalogue for further information.

We realise that, except for the most well-known astronomical objects, astro:name: doesn’t necessarily give a lot more context to a photo. We’re therefore interested in associating objects with constellations. The celestial sphere is divided into 88 constellations, defined by the International Astronomical Union. Each point on the sky belongs to a single constellation. We can use astro:RA and astro:Dec to associate each photo with a constellation, opening up the possibility of something like Flickr Places on the sky.

We’ve already experimented with overlaying Astronomy Photographer of the Year photos in Google Sky (http://www.nmm.ac.uk/visit/exhibitions/astronomy-photographer-of-the-year/showcase/); we’d like to take this further in the 2010 exhibition.

We’re hoping that astrotagging will become an accepted and widely-used standard for describing astrophotography. It’s already been integrated in LookUP (http://www.jodcast.net /lookUP/), a simple interface to a variety of astronomical name services, which was created by Stuart Lowe at the Jodrell Bank Centre for Astrophysics. And we recently extended the astrotagging standard to our own ‘Aurora chasers’ Flickr group. This is part of our citizen science project Solar Stormwatch (http://solarstormwatch.com): it asks aurora photographers to help scientists match up aurora with the solar storms that cause them. They do this by tagging their photos with a geotag, and with the astrotag for the full date and time they were taken.

Conclusion

The Astronomy Photographer of the Year programme gained momentum when the museum reached out to Flickr and its community of astrophotographers, developing a new standard for locating photos of space, and working with the scientists at Astrometry to develop an astrotagging bot. It could only have been delivered with the generosity of our collaborators at Flickr and Astrometry. As recession and funding pressures threaten to constrain museum programmes, this project shows how big ideas can be realised through creative approaches to free platforms. Our community, competition Web site, sophisticated judging interface and interactive exhibit were all developed using Flickr as a platform. According to Flickr’s developers, “the integration is so seamless... you might as well consider Flickr to be their 'backend' server.”

Acknowledgements

Our colleagues at the Royal Observatory, including Adrian MacTaggart, Ben Raithby, Dan Matthews, Dewar McAdam, Harvey Edser and Jim O’Donnell; the people at Flickr, especially Fiona Miller; the Astrometry.net team, including Christopher Stumm, Sam Roweis (University of Toronto), David W. Hogg (New York University), Dustin Lang (University of Toronto), Keir Mierle (University of Toronto) and Jon Barron.

References

Carnig, J. (2005). “Astronomers interpret Hubble images in same majestic light as early painters of America’s western landscapes”. The University of Chicago Chronicle, Vol. 24, No. 11, last updated March 2005. Consulted 31 January 2010. http://chronicle.uchicago.edu/050303/hubble.shtml

Daily Mail (2009). "Wonders of the cosmos: Photographers turn their eyes to the sky at night and capture the magic of deep space", Daily Mail online. Last updated 18 September 2009. Consulted 31 January 2010. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-1211764/Lost-space-Astronomy-photographers-capture-cosmic-masterpieces.html

Davis, L. (2009), "The Best Space Porn of the Year", io9 blog post. Last updated 9 September 2009. Consulted 31 January 2010. http://io9.com/5355974/the-best-space-porn-of-the-year/gallery/

Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York University Press, New York and London

Kandalgaonkar, N. (2009), Tags in space, Flickr developers blog. Last updated 20 March 2009. Consulted 31 January 2010. http://code.flickr.com/blog/2009/03/20/tags-in-space/

Oates, G. (2008), UK Museums and the Web. Last updated June 2008. Consulted 31 January 2010. http://www.slideshare.net/george08/uk-museums-and-the-Web

Rosso, A. and D. Peacock (2009). Great Expectations: Sustaining Participation in Social Media Spaces. Last updated January 2009. Consulted 31 January 2010. http://www.archimuse.com/mw2009/papers/russo/russo.html

Smith, R. (2009). NASA Blueshift [podcast]. The Science of Pretty Pictures. Last updated August 2009. Consulted 31 January 2010. http://astrophysics.gsfc.nasa.gov/outreach/podcast/wordpress/index.php/2009/08/31/podcast-the-science-of-pretty-pictures/

Straup Cope, A. (2009). Discussing machine tags in Flickr API. Flickr Discussion. Last updated August 2009. Consulted 31 January 2010. http://www.flickr.com/groups/api/discuss/72157594497877875/

Straup Cope, A. (2009). extra:extra=extra, Flickr developer blog. Last updated, July 2009. Consulted 31 January 2010. http://code.flickr.com/blog/2009/07/06/extraextraextra/

Straup Cope, A. (2009).The Interpretation of Bias (and the Bias of Interpretation). Last updated January 2009. Consulted 31 January 2010. http://www.archimuse.com./mw2009/papers/cope/cope.html

Trant, J. (2009). “Tagging, Folksonomy and Art Museums: Early Experiments and Ongoing Research”. Journal of Digital Information. Vol 10, No 1 (2009). Available at: http://journals.tdl.org/jodi/article/view/270/277

Wyatt, R. (2008). “Visualising Astronomy: The Astronomical Image. Part One”, CAP Journal, Communicating Astronomy with the Public, Issue 3 (page 34-35). Last updated May 2008. Consulted 31 January 2010. http://www.capjournal.org/issues/03/03_34.php