![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Archives & Museum Informatics

158 Lee Avenue

Toronto Ontario

M4E 2P3 Canada

ph: +1 416-691-2516

fx: +1 416-352-6025

info @ archimuse.com

www.archimuse.com

| |

Search A&MI |

Join

our Mailing List.

Privacy.

published: March 2004

analytic scripts updated:

October 28, 2010

Using Cinematic Techniques in a Multimedia Museum Guide

M. Zancanaro, O. Stock, and I. Alfaro, ITC-irst Italy

Abstract

In this paper we introduce the idea of enhancing the audio presentation of a multimedia museum guide by using the PDA screen to travel throughout a fresco and identify the various details in it. During the presentation, a sequence of pictures is synchronized with the audio commentary, and the transitions among the pictures are planned according to cinematic techniques.

The theoretical background is presented, discussing the language of cinematography and the Rhetorical Structure Theory to analyze dependency relationships inside a text. In building the video clips, a set of strategies similar to those used in documentaries was employed. Two broad classes of strategies have been identified. The first class encompasses constraints imposed by the grammar of cinematography, while the second deals with conventions normally used in guiding camera movements in the production of documentaries.

The results of a preliminary evaluation are also presented and discussed.

Keywords: Multimedia Museum Guides, Cinematography, Interaction on Small Devices, Location-awareness

1. Introduction

Many research projects are exploring the new possibilities offered by Personal Digital Assistants (PDAs) in a museum setting (for example, see Grinter et al, 2002, Cheverst 2000 and Not et al., 1998). Usually, these multimedia guides use static images, while others employ pre-recorded short video clips about museum exhibits. In a previous work (Not et al, 1998, 2000), we explored different techniques to automatically build multimedia, location-aware presentations in a museum setting. The advent of more powerful devices has allowed researchers to experiment with new forms of multimedia, in particular time-based media such as animations.

In this paper we introduce the idea of enhancing the audio presentation (dynamically assembled pre-recorded or synthesized speech) of a complex fresco by using the PDA screen to travel throughout the fresco itself and identify details. At presentation time, a sequence of pictures is synchronized with the audio commentary, and the transitions among them are planned according to cinematic techniques. Our hypothesis is that the use of this type of animation to present the description of a painting allows the visitor to better identify the details introduced by the audio counterpart of the presentation. In this manner, both the efficiency and the satisfaction dimensions of the system usability are increased (Nielsen, 1994) while also providing an enhanced learning experience for the visitor.

The language of cinematography (Metz, 1974), including shot segmentation, camera movements and transition effects, is employed in order to plan the animation and to synchronize the visual and the verbal parts of the presentation. In building the animations, a set of strategies similar to those used in documentaries was thus employed. Two broad classes of strategies have been identified. The first class encompasses constraints imposed by the grammar of cinematography, while the second deals with conventions normally used in guiding camera movements in the production of documentaries. For instance, a strategy in the first class would discourage a zoom-in immediately followed by a zoom-out, while a different strategy in the second class would recommend the use of sequential scene cuts, rather than a fade-out effect, to visually enumerate different characters in a scene. It is worth noting that in the latter strategy it is often necessary to make reference to the discourse structure of the audio part of the presentation, such as enumeration of properties, background knowledge, and elaboration of related information. In order to formally use discourse structure, we employ the Rhetorical Structure Theory (Mann and Thompson, 1987).

At present, we have completed a first prototype of a multimedia guide that employs cinematic techniques in presenting information for a fresco at Torre Aquila in Trento, Italy. A Web-based simulation of the multimedia guide can be seen at http://peach.itc.it/preview.html.

The next section briefly discusses the issues in designing a multimedia museum guide. Section 3 introduces the features of the Torre Aquila prototype. Sections 4 and 5 present the theoretical background, discussing respectively the relevant concepts for the language of cinematography and the Rhetorical Structure Theory to analyze dependency relationships inside a text. Section 6 illustrates the strategies used in our multimedia guide to produce effective and pleasant video clips starting from audio commentaries. Finally, in section 7, the results of a preliminary evaluation are presented and discussed.

2. The Museum as a Smart Environment

Museums and cultural heritage institutions recreate an environment conducive to exploring not only the exhibited objects and works of art, but also new ideas and experiences. Visitors are free to move around and learn concepts, inquire and even apply what is leaned to their own worldview. A museum visit is thus a personal experience encompassing both cognitive aspects, such as the elaboration of background and new knowledge, and emotional aspects that may include the satisfaction of interests or the fascination with the exhibit itself. Despite the inherently stimulating environment created by cultural heritage institutions, on their own they often fall short of successfully supporting conceptual learning, inquiry-skill-building, analytic experiences or follow-up activities at home or the school (Semper and Spasojevic, 2002).

The optimal multimedia tourist guide should support strong personalization of all the information provided in a museum in an effort to ensure that each visitor be allowed to accommodate and interpret the visit according to his own pace and interests. Simultaneously, a museum guide should also provide the appropriate amount of impetus to foster learning and self-development so as to create a richer and more meaningful experience.

In order to achieve the above goals it is necessary that the information be presented in a manner that is appropriate to the physical location of the visitor as well as to the location of the works of art within the environment. Smoothly connecting the information found in an exhibit and presenting it to the visitor in a flexible yet coherent manner with respect to his physical location can mazimize the overall experience and absorption of new information for the viewer (Stock and Zancanaro, 2002). In other words, if the information is provided in a manner that flows and relates pieces to each other, this process in and of itself can aid in stimulating the visitor's interest and, hence, desire to inquire, analyze and learn. This idea relates to the concept of situation-aware content, where information is most effective if presented in a cohesive way, building on previously delivered information. This may be accomplished by using comparisons and references to space and time, which in turn may aid the visitor in becoming oriented within the museum as well as across the various works of art.

The ideal audio guide should not only guess what the visitors are interested in, but also take into consideration what they have to learn: orienting visitors, providing opportunities for reflection and allowing them to explore related ideas, thereby greatly enhancing the visit's educational value. In essence, the guide should stimulate new interests and suggest new paths for exploring the museum. A system that supports visitors in their visit should take into account their agenda, expectations and interests as well as the peculiarities of a cultural experience in a physical environment.

It is essential to also consider the importance of creating an overall experience that truly addresses the needs of a person visiting a museum. This requires not only providing the visitor with a vast amount of information, even if wonderfully presented, but also allowing the person to spend a pleasurable and entertaining time at the exhibit. The concept of the immersive environment addresses the importance of creating a technology that supports rather then overwhelms the real experience of visiting a museum. A museum guide of this nature must be able to create a balance in terms of attention required from the visitor, also allowing time to be spent enjoying the "romance" of the cultural heritage institution and the works found therein.

These and other challenges come into play when designing a system for the entertainment and edutainment of museum visitors. Creating an electronic tourist guide that transforms the user experience from one of simple consultation (commonly achieved with audio guides, multimedia kiosks, CDROMs or even books) to an immersion into a rich information environment indeed requires a careful examination of all the abovementioned factors, while also considering input from visitors themselves. Difficulties arise when observing that such systems are not intended to help users perform specific work-related tasks, and most of the time they cannot be brought back to clearly stated user requirements. Keeping in mind that the ultimate goal of a guide is to engage the user and to stimulate learning, it becomes clear that the nature of this kind of system imposes a balance between the designer's vision and user needs.

Using animations or video clips enhance the richness of the interaction though these may also distract the user by calling attention to the device rather than to the exhibit itself. Our hypothesis is that, on the contrary, a carefully planned video clip describing the exhibit will actually help the visitor quickly localize the details of the painting as well as aid the flow of the presentation by illustrating the relationship between new and already presented information.

3. The Prototype at Torre Aquila

We have applied the idea of using cinematic techniques for presenting details of artworks in a prototype of a multimedia guide for Torre Aquila' a tower at the Buonconsiglio Castle in Trento, where a fresco called "The Cycle of the Months", a masterpiece of the gothic period, is found. This fresco, painted in the Fifteenth Century, illustrates the activities of aristocrats and peasants throughout the year. The fresco is composed of eleven panels, each one representing one month (the month of March was destroyed over time) and occupies the four walls of the tower (see figure 1).

Figure 1: Torre Aquila and the grid of infrared

Our multimedia guide, implemented with Macromedia Flash on a PDA, detects the position of the visitor by means of infrared emitters placed in front of each panel. Interaction with the system is both proposed by the system itself and accepted by the user, thus sharing the responsibility of information access. When the system detects that the visitor is in front of one of the four walls, a picture of that wall is displayed on the PDA and, after a few seconds, if the user has not changed position, that panel is highlighted (see figure 2). At this point, the visitor can click on the panel and receive a multimedia presentation of the panel chosen.

Figure 2: Snapshots of the multimedia guide localizing the user.

The multimedia presentation is composed of an audio commentary accompanied by a sequence of images that appear on the PDA display and help the visitor quickly identify the fresco's details mentioned in the commentary. For instance, when a specific detail of the panel is explained by the audio, the PDA may display or highlight that detail, thus quickly calling the attention of the user to the area in question.

During the presentation, the PDA displays a VCR-style control panel and a slide bar to signal the length of the video clip and its actual position (see figure 3). At any given moment, the user is free to pause, fast forward, rewind and even stop the presentation by tapping on the appropriate control panel button. In this manner, the visitor is able to control the speed as well as the information itself, while also revisiting sections found most interesting.

Figure 3: Snapshot of the multimedia guide playing a video clip.4.

The Language of Cinematography

According to Metz {1974), cinematic representation is not like a human language that is defined by a set of grammatical rules; it is nevertheless guided by a set of generally accepted conventions. These guidelines may be used for developing multimedia presentations that can be best perceived by the viewer. In the following, we briefly summarize the basic terminology of cinematography. In section 6 we will discuss how these conventions can be expressed both in terms of constraints on camera movements and in terms of strategies related to the discourse structure of the associated audio commentary.

4.1 Shot and camera movements

The shot is the basic unit of a video sequence. In the field of cinematography a shot is defined as a continuous view from a single camera without interruption. Since we only deal with still images, we define a shot as a sequence of camera movements applied to the same image.

The basic camera movements are pan, from "panorama", a rotation of the camera along the x-axis, tilt, a rotation along the y-axis, and dolly, a rotation along the z-axis.

4.2 Transition effects

Transitions among shots are considered the punctuation symbols of cinematography; they affect the rhythm of the discourse and the message conveyed by the video.

The main transitions used are cut, fade, and cross fade. A cut occurs when the last frame of a shot is immediately replaced by the first frame of the following shot. A fade occurs when one shot gradually replaces another one, either by disappearing (fade out) or by being replaced by the new shot (fade in). A particular case of a fade happens when instead of two shots, there is one shot and a black screen that can be, again, faded in or faded out. Finally, a cross fade (also called dissolve) occurs when two shots are gradually superimposed during the moment when one is faded out while the other is faded in.

5. Rhetorical Structure Theory

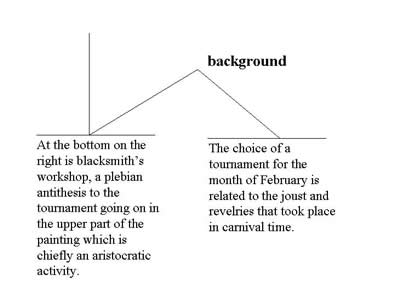

Rhetorical Structure Theory (Mann and Thompson, 1987) analyses discourse structure in terms of dependency trees, with each node of the tree being a segment of text. Each branch of the tree represents the relationship between two nodes, where one node is called the nucleus and the other is called the satellite. The information in the satellite relates to that found in the nucleus in that it expresses an idea related to what was said in the nucleus. This rhetorical relation specifies the coherence relation that exists between the two portions of text contained in the nodes. For example, a Cause rhetorical relation holds when the satellite describes the event that caused what is contained in the nucleus. Figure 4 shows an example of a rhetorical tree. Here the second paragraph provides background information with respect to the content expressed in the first paragraph. This additional information acts as a sort of reinforcement for what was previously said in the first paragraph and consequently facilitates the absorption of information. In the original formulation by Mann and Thompson, the theory posited twenty different rhetorical relations between a satellite and a nucleus, while other scholars have since added to this theory.

Figure 4: An example of a rhetorical tree (simplified).

RST was originally developed as part of work carried out in the computer-based text generation field. In a previous work (Not and Zancanaro, 2001), we described a set of techniques to dynamically compose adaptive presentations of artworks from a repository of multimedia data annotated with rhetorical relations. These techniques have been exploited in an audio-based, location-aware adaptive audio guide described in Not et al., {2000). The audio commentaries produced by this audio guide are automatically annotated with the rhetorical structure. In the next section we will discuss how this information can be used to create more effective video clips to accompany the commentary.

6. Video Clips on Still Images

Video clips are built by first searching for the sequence of details mentioned in the audio commentary, deciding the segmentation in shots, and then planning the camera movements in order to smoothly focus on each detail in synchrony with the verbal part.

In building a video clip, a set of strategies similar to those used in documentaries is employed. Two broad classes of strategies have been identified. The first class encompasses constraints imposed by the grammar of cinematography, while the second deals with conventions normally used in guiding camera movements in the production of documentaries.

While the constraints are just sequence of forbidden camera movements, the conventions are expressed in terms of rhetorical structures found in the audio commentary. In our view, the verbal part of the documentary always drives the visual part.

6.1 Constraints on Camera Movements

In order to ensure a pleasant presentation, constraints on camera movements have to be imposed. For example, a pan from right to left forbids a subsequent pan from left to right. In general, applying any given movement (pan, tilt and zoom) and then immediately reapplying it on the reverse direction is discouraged because this action renders the video uncomfortable to watch.

Given that the audio commentary drives the visual part, it is often the case that such forbidden combinations of camera movements are required. In these cases, two tricks can be applied: either choosing a different way of focusing the detail required by the verbal part; for example a zoom out can often effectively replace a pan, or starting a new shot altogether. In the latter case, the two shots should be linked by a transition effect that suggests continuity, such as a short fade.

Rhetorical Strategies

Constraints on camera movements alone are sufficient to ensure a pleasant presentation, yet they do not impact the effectiveness of the video clip. In order to have a more engaging presentation, the visual part should not only focus on the right detail at the right time, but also support the presentation of new audio information by illustrating its relation to information that has been already given. In this manner, continuity between the pieces of information is built, and in turn facilitates the viewing of the video clip while stimulating the absorption of new information.

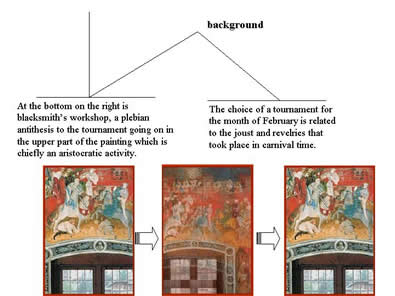

The text in figure 5 can be visually represented with two shots of the same image (that is, the tournament) linked by a long cross fade. Technically, having two shots is not necessary, since the image is the same, but the cross fade helps the user understand that background information is going to be provided. The first image is thus presented while the first paragraph is heard over the audio; then when the audio switches to, in this case, the background information, the image is enlarged to cover the entire panel and finally is refocused on the detail once the audio has stopped.

Figure 5: The "Tournament" example: from the text to the video clip.

A rhetorical strategy suggests, on the basis of a rhetorical tree configuration, what shot segmentation and which transition effect should be applied. The strategies employed in the Torre Aquila multimedia guide were elicited by a focus group activity with a documentary director.

7. Preliminary Evaluation

A formal evaluation of the prototype will start next March at Torre Aquila. Preliminary studies and pilot tests show encouraging results and interesting effects.

All users became acquainted with the system very quickly. Most of them used the PDA as a "3D mouse", pointing directly to the infrared emitters to speed up the localization. Future investigations will evaluate how users can be more directly involved in the process of localization.

Most of the users complained before actually using the system that a video sequence on a PDA would distract their attention from the real artwork. After a short interaction with the system, however, they appreciated the possibility of quickly localizing small details on the fresco. This demonstrates that use of cinematic techniques in a multimedia guide can be effective, particularly in explaining complex painting. The different effects that the verbal and the visual parts of the presentation have on the user's attention are yet to be investigated.

8. Conclusion

This paper discussed how cinematic techniques can be used in a multimedia museum guide to provide more pleasant and effective presentation of information. Video clips are built by first searching for the sequence of details mentioned in the audio commentary, deciding the segmentation in shots, and then planning the camera movements soas to smoothly focus on each detail in synchrony with the verbal counterpart. In our approach, the verbal part always drives the visual part.

The video clips are built accordingly to two broad classes of strategies. The first class encompasses constraints imposed by the grammar of cinematography, while the second deals with conventions normally used in guiding camera movements in the production of documentaries.

While the constraints are just a sequence of forbidden camera movements, the conventions are expressed in terms of rhetorical structures found in the audio commentary. By coupling these cinematic techniques into organized guidelines, the creation of multimedia video clips can vastly help to improve quality as well as the effectiveness of the presentations. A visitor to a museum can thus benefit from an automatic guide that causes minimal interference with the enjoyment and learning experience provided by an exhibit.

As a case study, a multimedia museum guide for Torre Aquila in Trento has been presented and the results of a preliminary evaluation have been discussed

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by the PEACH and TICCA projects, funded by the Autonomous Province of Trento.

References

Metz 1974. Film Language: a Semiotics of the Cinema. Oxford University Press, New York.

Cheverst, K., N. Davies, K. Mitchell, A. Friday and C. Efstratiou, 2000. Developing a Context-aware Electronic Tourist Guide: Some Issues and Experiences Proceedings ofCHI 2000. Amsterdam.

Grinter, R.E., P. M. Aoki, A. Hurst, M. H. Szymanski, J. D. Thornton and A. Woodruff, 2002. Revisiting the Visit: Understanding How Technology Can Shape the Museum Visit. In Proc. ACM Conf. on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, New Orleans, LA.

Mann, W.C. and S. Thompson, 1987. Rhetorical Structure Theory: A Theory of Text Organization, In L. Polanyi (ed.), The Structure of Discourse, Ablex Publishing Corporation.

Nielsen, J. 1994. Usability Engineering, Morgan Kaufmann, San Francisco.

Not, E., D. Petrelli, O. Stock, C. Strapparava and M. Zancanaro, 2000. The Environment as a Medium: Location-aware Generation for Cultural Visitors. In Proceedings of the workshop on Coherence in Generated Multimedia, held in conjunction with INLG'2000, Mitze Ramon, Israel.

Not, E., D.Petrelli , M. Sarini, O. Stock, C. Strapparava, M. Zancanaro, 1998. Hypernavigation in the Physical Space: Adapting Presentations to the User and the Situational Context. In New Review of Hypermedia and Multimedia, vol. 4.

Not and Zancanaro, 2001. E. Not, M. Zancanaro. "Building Adaptive Information Presentations from Existing Information Repositories". In Bernsen N.O., Stock O. (eds.), Proceedings of the International Workshop on Information Presentation and Multimodal Dialogue, Verona, Italy.

Semper, R.,and M. Spasojevic, 2002. The Electronic Guidebook: Using Portable Devices and a Wireless Web-Based Network to Extend the Museum Experience. In Proceedings of Museums and the Web Conference, Boston, MA.

Stock, O., M. Zancanaro. Intelligent Interactive Information Presentation for Cultural Tourism. Invited talk at the International Workshop on Natural, Intelligent and Effective Interaction in Multimodal Dialogue Systems. Copenhagen, Denmark. June, 2002.